Listen to this article (AI-generated narration)

Twenty years. That’s how long I’ve been writing code professionally. Two decades of watching tools get better, abstractions get loftier, and predictions of our impending obsolescence get louder. Every time I see another headline declare, “AI will replace programmers,” I feel like I’m watching a rerun. Because I’ve seen this episode before. Multiple times, actually.

COBOL was supposed to let managers write their own programs (spoiler: they didn’t). Visual Basic was baptized as the one to democratize software engineering (it didn’t). Low-code platforms would let non-programmers build their own applications (we’re still waiting on that). Now? AI will finally do all the coding.

This pattern has been repeated for seven decades. The same promise, different technology. And yet, here we are, more software engineers than ever before, earning more money than ever before, building more than ever before.

I’ve been thinking about why we keep falling for this. Not just as an industry, but as a profession. What do seven decades of failed predictions tell us about what we actually do? Because if everyone keeps getting it wrong, maybe we’ve been thinking about software engineering all wrong.

Before computers were machines, they were people

Computer used to be a job title. Not a machine, but a person. People who spent their days doing manual calculations by hand. Rooms full of them, actually, doing the calculations that made scientific breakthroughs possible.

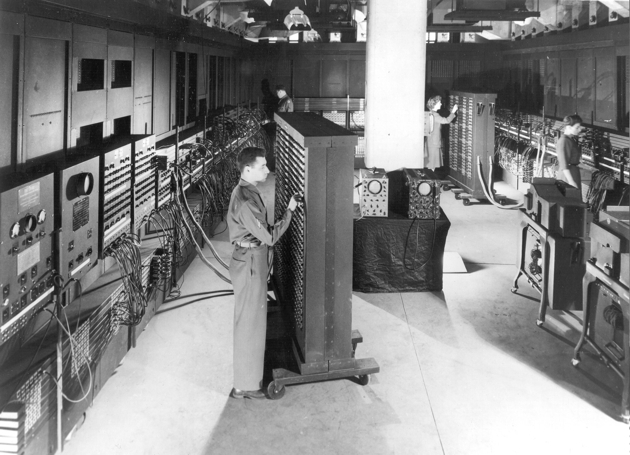

The origin story is surprisingly specific. In 1757, French mathematician Alexis-Claude Clairaut needed to predict when Halley’s Comet would return. The calculations were enormous, so he divided the work among three people. That simple act of breaking down complex calculations into manageable, repeatable tasks is what we are doing today. Only with different tools. These human computers became critical infrastructure. They calculated trajectories for space missions, catalogued stars, and crunched numbers that enabled major discoveries. When ENIAC, the first general-purpose electronic computer needed operators in 1945, they recruited from this human computer pool. Without programming languages, manuals, or Stack Overflow to copy from, they figured it out from scratch. They created the first debugging techniques, invented the first programming practices, and built the foundation we still use.

The ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), the first general-purpose electronic computer, 1945. U.S. Army Photo, public domain.

The ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), the first general-purpose electronic computer, 1945. U.S. Army Photo, public domain.

Notice what happened: the transition from human to electronic computing did not eliminate the need for people who understood how to break down problems into executable steps. It just changed the medium. Remember that; it will keep coming up.

When English-like code would replace programmers

The 1950s brought the first wave of “programming is about to get so easy, we won’t need programmers anymore” predictions. The pitch sounds eerily familiar.

COBOL was supposed to change everything. Grace Hopper, one of its creators, had a vision: “Data processors ought to be able to write their programs in English, and the computers would translate them into machine code.” Managers would write their own programs. English-like syntax would make programming accessible to anyone. Specialized programmers? Unnecessary. Reading this today is like watching the tweets about AI hype from 2023, only in a different font.

FORTRAN had promised the same. IBM’s 1956 manual declared that “a considerable reduction in the training required to program.” John Backus, FORTRAN’s creator, described pre-FORTRAN programming as “hand-to-hand combat with the machine, with the machine often winning.” His language would end that struggle, opening programming to “anyone willing to learn a basic language.”

The entire “automatic programming” movement was built on this dream. Grace Hopper’s A-0 compiler would allow computers to write programs automatically. Industry experts were convinced that high-level languages would make programmers obsolete within a decade.

What actually happened? These tools didn’t replace programmers; they created an avalanche of them. As Ken Thompson noted, FORTRAN enabled “95 percent of the people who programmed in the early years [who] would never have done it without FORTRAN.” Better tools didn’t eliminate jobs. They expanded the market.

The predictions missed something fundamental: most people don’t know how to explain a problem in sufficient detail to get a working solution. That gap between “I want the computer to do X” and “exactly how to make the computer do X”—that’s the entire job. COBOL being “English-like” didn’t magically bridge that gap. Business users found it “too tough to learn” (their words, not mine). Even engineers needed help with syntax supposedly designed for non-engineers. The pattern was set: promise simple tools for everyone, deliver powerful tools for the professionals.

Grace Hopper at the UNIVAC keyboard, circa 1960. Public domain.

Grace Hopper at the UNIVAC keyboard, circa 1960. Public domain.

But the industry wasn’t done making promises.

The software crisis and the tools that couldn’t fix it

By the 1970s, the software engineering profession faced a new challenge, and with it, a new wave of “solutions.” Software was eating the world, but it was also breaking the world. Projects routinely ran over budget and schedule. Some software failures caused actual property damage and loss of life. This was dubbed the “software crisis,” and formalized at the 1968 NATO Software Engineering Conference. The industry was desperate for solutions. Enter Fourth Generation Languages (4GLs) and Computer-Aided Software Engineering (CASE) tools, promising productivity improvements of 10x to 100x.

The pitch was familiar: finally, end users could program their own applications. No more software engineer bottlenecks. James Martin wrote a whole book in 1981 called “Application Development Without Programmers.” His thesis was stark: “The number of software engineers available per computer is shrinking so fast that most computers in the future will have to work at least in part without software engineers.”

The products that emerged made massive claims. PowerBuilder promised a “revolution in productivity” so compelling that Sybase paid $940 million for its creator in 1994.

A telling example: The Santa Fe railroad adopted MAPPER, a fourth-generation language, because they believed, “It was easier to teach railroad experts to use MAPPER than to teach software engineers the intricacies of railroad operations.”

This logic sounds reasonable until you realize the fundamental flaw: domain experts know what they want the computer to do, but they don’t know how to tell the computer to do it. Those are completely different skills.

CASE tools escalated this automation fantasy. The market exploded to $12.11 billion by 1995, with over 100 companies offering nearly 200 different tools. The U.S. government alone spent millions chasing the promise of automated code generation.

The crash was spectacular. A 1993 GAO report found “Little evidence yet exists that CASE tools can improve software quality or productivity.” The tools were complicated, memory-hungry, and had massive learning curves that — surprise! —still required programming knowledge.

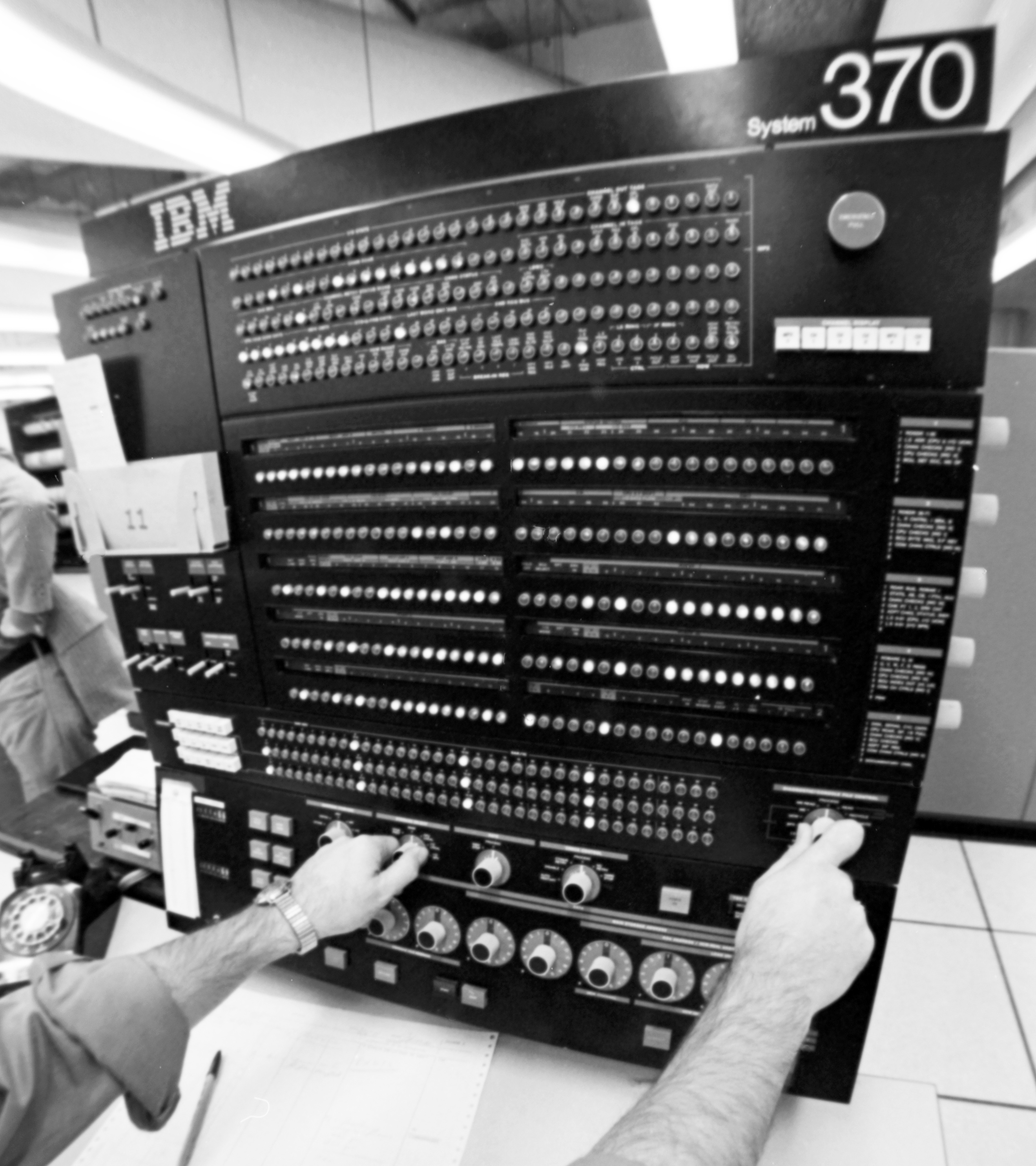

IBM System/370 mainframe computer, 1970s. Public domain.

IBM System/370 mainframe computer, 1970s. Public domain.

Are you starting to see a pattern?

When pointing and clicking would replace typing

By the 1990s, the industry had a new theory: we had been wrong all along. The problem was text-based programming – even simplified text-based programming. Solution? Get rid of the text completely. Visual programming and drag-and-drop interfaces will finally make code-free programming a reality. (Yes, that’s what people were saying.)

Microsoft’s Visual Basic launched in 1991 with the tempting promise of creating Windows applications quickly, “without the steep learning curve associated with C or C++.” Borland’s Delphi and IBM’s VisualAge followed. InfoWorld gushed that VisualAge would “reduce the cost and effort associated with building and maintaining Java applications.”

The entire Rapid Application Development (RAD) methodology was built on this vision. Guess who’s back with a new book? James Martin — remember him from “Application Development Without Programmers”? He was now promising development time would drop from months to weeks or days. Visual form designers would eliminate complex GUI coding. Business users would build applications themselves. Industry consensus was clear: visual programming was “the future of software engineering,” and text-based coding would be obsolete within a decade. (I’m starting to notice a pattern here. Are you?)

The poster child for this vision was General Magic, which was spun off from Apple in 1990 by original Macintosh team members including Bill Atkinson and Andy Hertzfeld. They were building “Personal Internet Communicators” – basically smartphones before the infrastructure existed. Their Magic Cap OS featured room-based metaphors where you could program entirely through visual manipulation. No traditional coding required. It was a revolutionary vision. Only 3,000 Sony Magic Link devices were sold, mostly to family and friends. (Ouch.)

The decline of visual programming? Complexity. Simple visual representations became overwhelmingly fast for real applications. A single line of code mapped to multiple visual elements. Visual “spaghetti code” was actually harder to follow than text. And abstraction? The entire point of programming? Became nearly impossible in visual formats. Even worse was the “property dialog programming” that researchers identified. Visual elements became containers for hidden textual code. Most of the real logic ended up buried in dialog boxes and property sheets. You got the worst of both worlds: visual overhead plus textual complexity underneath. Congratulations, you played yourself.

Academic research confirmed what developers already knew: it takes longer to read graphical programming notation than it does text. The human brain processes text more efficiently for complex logical operations. (Turns out evolution optimized our brains for reading text over thousands of years. Who knew?)

The kicker: during the dot-com boom, tech employment shot up 36% from 1990 to 2000. If visual programming had truly democratized software engineering, this shortage would have been eliminated. Instead, the demand for traditional software engineers grew exponentially.

Visual tools didn’t eliminate software engineers. They just gave software engineers better tools. Same pattern, different decade. You’d think, after decades of failed predictions, the industry would recognize the pattern. Instead, it just got better at marketing.

Low-code platforms and the last mile problem

By the 2000s, the industry learned a key lesson about how to sell the same promise: rebranding. Visual programming became “low-code/no-code” platforms. The promise was the same: anyone could eventually build applications. But this time, they gave non-engineers a better title: “citizen developers.”

This was my era. I started learning to code and working professionally as a software engineer in the mid-2000s and watched this movement unfold with my own eyes. I got to see the gap between marketing decks and production reality up close and I have come to admire the marketing ingenuity of “citizen developer”. It sounds so much more empowering than person who’s about to create a maintenance nightmare that will haunt us for years.

Forrester Research coined the term “low-code” in 2014, and the market exploded. OutSystems hit a $9.5 billion valuation in 2021. In 2018, Siemens paid $700 million for Mendix. Microsoft, Google, and Salesforce all launched competing platforms. Money was flying everywhere. Gartner made some particularly bold predictions. By 2025, they predicted, “Citizen developers at large enterprises will outnumber professional software developers by a factor of 4:1.” Also, “70% of new applications developed by organizations will use low-code or no-code technologies.”

So. How’d that work out?

Well, 69% of IT executives now consider shadow IT a major concern. 30-40% of IT spending goes to unauthorized applications (what’s euphemistically called “shadow IT” instead of “unauthorized security nightmares”). The average cost of a single security breach reached $4.88 million in 2024. So… not great, Bob.

The problem has a name: the “last mile problem.” Low-code platforms handle about 80% of application needs easily. But that remaining 20% — complex integrations, custom business logic, performance optimization, security, and long-term maintenance — still needs the expertise of professional developers.

It’s like learning piano. Many people can play chopsticks, some folks can play beautiful music, and a select few are concert pianists. The instrument is the same, but as complexity increases, it requires a certain level of skill.

Despite all the predictions of software engineer obsolescence, the global developer population grew from 26.3 million in 2020 to 28.7 million in 2024, according to Evans Data Corporation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 17.9% growth for software developers through 2033. Meanwhile, salaries have continued to rise —the median jumping from $95,000 in 2015 to $148,393 in 2023. Low-code platforms found their place, but not as software engineer replacements. They have become tools that increase the productivity of professional developers. With very careful governance. Because left unchecked, they create security disasters.

Which brings us to today’s iteration of the eternal promise.

AI coding assistants and the trust paradox

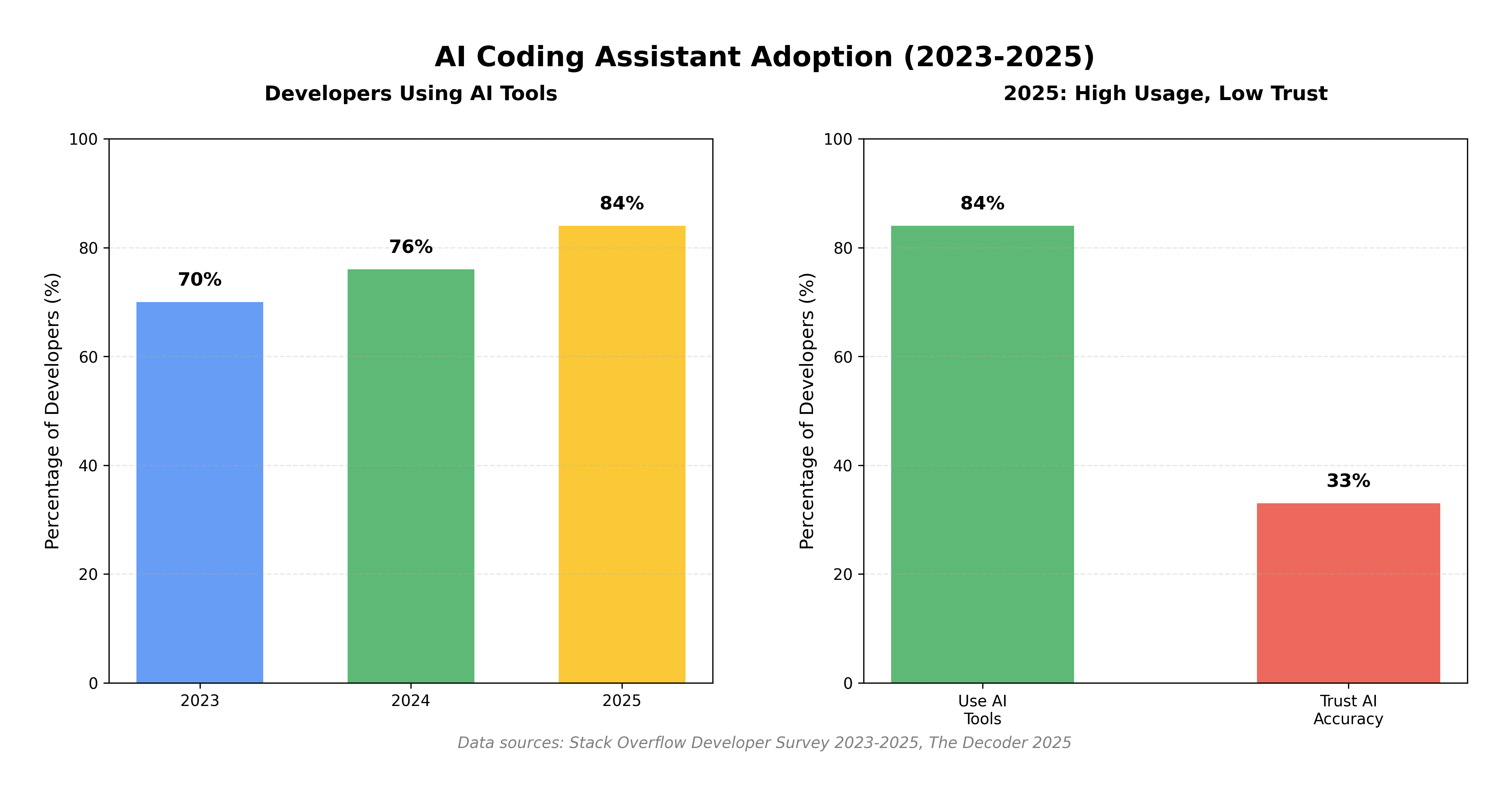

And here we are. AI coding assistants like GitHub Copilot, ChatGPT, and Claude are here, and the familiar chorus has begun: This time it’s different. This time, software engineers really will be replaced. I’ll be honest; AI tools are genuinely impressive. I use them daily. GitHub Copilot has been adopted by over 50,000 organizations, including one third of Fortune 500 companies. Developers report coding 55% faster and feeling more fulfilled. The tools have a 27% suggestion acceptance rate and produce measurably more pull requests. These aren’t toy demos. They’re production tools that actually work. However, while AI tool usage has grown to 84% in 2025 (up from 70% in 2023), trust actually fell to 33%, down from 43% the previous year. Nearly half of developers (46%) actively distrust the accuracy of AI tools. And unsurprisingly, most developers do not see AI as a threat to their jobs. We’re using the tools more, trusting them less, and not worried about being replaced. Interesting.

Even industry leaders are lowering their expectations. IBM CEO, Arvind Krishna has challenged the predictions of 90% of AI-written code, saying, “I think the number is going to be more like 20-30% of the code could get written by AI, not 90%.” His insight echoes historical patterns: “If you can do 30% more code with the same number of people… the most productive company gains market share.”

More productivity doesn’t mean fewer jobs. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman explains why: “The world wants a gigantic amount of more software, 100 times maybe a thousand times more software.” When software engineers become 10x more productive, guess what? More software gets built. And the salaries of software engineer keep rising.

The reason is the same as it’s always been: software engineering isn’t just generating code. It’s understanding business requirements, making architectural decisions, solving creative problems, exercising quality judgment, communicating with stakeholders, and navigating ethical considerations. AI excels at code completion and pattern recognition. But, it struggles with the contextual understanding and judgment that define professional software engineering. There’s even a term now for the fantasy that AI can generate entire applications from simple prompts: “vibe coding.” 72% of developers reject this as not part of professional work. (And if you’ve tried to build anything real with just prompts, you know why.)

The same formula, different decade. Impressive tools that make software engineers more productive, not tools that replace software engineers.

AI coding assistant adoption has surged from 70% to 84% (2023-2025), but developer trust has declined to just 33%. Data: Stack Overflow Developer Survey, The Decoder.

AI coding assistant adoption has surged from 70% to 84% (2023-2025), but developer trust has declined to just 33%. Data: Stack Overflow Developer Survey, The Decoder.

The essential complexity that never goes away

So why does this pattern keep repeating? Why does every technological leap trigger the same predictions, only to produce the same results? The answer had been written nearly four decades earlier. In 1986, Fred Brooks wrote an essay that basically predicted everything we’ve just witnessed. In the paper, “No Silver Bullet” Brooks argued there’s “no single development, in either technology or management technique, which by itself promises even one order of magnitude improvement within a decade.”

Nearly four decades later, every prediction we’ve covered proves his point.

Every.

Single.

One.

Brooks distinguished between accidental complexity and essential complexity in software engineering. Accidental complexity is what we create by using poor tools or methods – that can be solved. Essential complexity is the inherent difficulty of the problem domain — that’s permanent. The kicker: AI tools, like all the tools before them, primarily address accidental complexity. They’re great at code completion, error detection, boilerplate generation. But essential complexity, understanding what to build, designing architectures, making trade-offs, knowing why something should work a certain way, that remains inexorably human.

Brooks identified four properties that make software inherently complex:

- Complexity: Non-linear interactions between components

- Conformity: Adapting to arbitrary external constraints

- Changeability: Constant evolution of requirements

- Invisibility: Lack of natural geometric representation

These properties don’t disappear with better tools. A modern analysis puts it perfectly: “Technologies like Rust, Kubernetes, and Generative AI bring significant advancements, they are not cure-alls for the inherent complexities of software engineering.”

Brooks’ Law makes another crucial point: “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” This explains why automation doesn’t simply scale. New team members need ramp-up time. Communication overhead grows exponentially. Many tasks resist parallelization. These dynamics also apply to AI adoption. The promise of instant productivity gains is contrasted with the reality of learning curves, integration challenges, and the constant need for human oversight.

AI tools deliver incremental improvements, not order-of-magnitude breakthroughs. They excel at reducing accidental complexity but cannot touch the essential complexity of understanding what to build and why. The fundamental nature of software engineering resists automation in ways that other fields simply don’t. And Brooks called this in 1986.

But there’s an even more surprising part of this story.

Better tools create more jobs, not fewer

Every wave of automation that was supposed to eliminate software engineers actually created more software engineering jobs. This isn’t a fluke. It’s a fundamental economic principle called induced demand that industry predictions consistently miss. And it’s been happening since the 1950s.

The numbers are staggering! In 2016, there were 21 million professional software engineers worldwide, reaching 26.9 million in 2022. In the United States alone, software developers now number 1.5 million—the largest computer/mathematical occupation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projected 25% growth between 2019-2029, much faster than average. Salaries reflected this sustained demand too illustrated by the median jumping from $95,000 in 2015 to an average of $148,393 in 2023. This growth happened despite—or rather, because of—successive automation waves:

- Assembly language → high-level languages (1950s-60s)

- Mainframes → personal computers (1970s-80s)

- Procedural → object-oriented programming (1980s-90s)

- Desktop → web development (1990s-2000s)

- Manual deployment → DevOps/CI/CD (2000s-2010s)

- Traditional development → AI-assisted programming (2020s)

Each wave was predicted to reduce software engineer need. Instead, each wave expanded the market.

Every.

Single.

Time.

The mechanism is called Jevons’ Paradox, which was originally observed in coal consumption. As efficiency improves, consumption rises rather than falls because lower costs enable new uses. In software, more efficient development means lower costs, which enables more projects, which creates more demand. AI making coding 30% more efficient doesn’t eliminate 30% of software engineers; it enables 30% more software to be built. The math works differently than people think.

This pattern transcends programming. Calculators didn’t eliminate mathematicians; they enabled more complex calculations. Desktop publishing didn’t eliminate designers; it created new design opportunities.

Since 1950, only one of 270 detailed occupations has been eliminated by automation. One. Can you guess what it was?

Elevator operators.

That’s it. That’s the list.

Modern AI continues this pattern. As IBM’s CEO notes, if AI enables “30% more code with the same number of people… the most productive company gains market share.” Thus, this creates competitive pressure to hire more developers, not less.

The bottleneck is not typing speed or syntax knowledge. It never was. It’s understanding what to build, why it matters, and how it should work. These are fundamentally human cognitive tasks that are resistant to automation.

The cycle continues

So, what do seven decades of failed predictions tell us about the nature of software engineering?

First, that these predictions follow a remarkably consistent pattern:

- Impressive demonstration

- Bold predictions

- Vendor promises of 10x productivity

- Analyst forecasts of software engineer obsolescence

- Early adopters discover hidden complexity

- Tools find niches but fail to replace software engineers

- Software engineer employment grows

- Next wave begins

Rinse.

Repeat.

For seventy years.

From COBOL’s English-like syntax to AI’s natural language interfaces, the core promise never changes: making programming so simple that software engineers are redundant.

These predictions consistently overestimate the capabilities of tools, while underestimating human value. They assume efficiency gains directly translate to job losses, ignoring induced demand. They focus on code generation while completely missing requirements analysis, architecture design, and stakeholder communication.

Most importantly, they confuse the elimination of tedious tasks for the elimination of the profession itself. (Writing code was never the hard part.). The pioneers understood this. Grace Hopper wanted to “bring another whole group of people able to use the computer easily”—not eliminate programmers but expand the field. John Backus created FORTRAN because he was “lazy” and “didn’t like writing programs.” He wanted to eliminate tedium, not programmers. Big difference.

Modern evidence supports their wisdom. Research on GitHub Copilot found that 60-75% of developers report feeling more fulfilled with their jobs and able to focus on more satisfying work when using AI tools. Seventy-three percent said the tools help them stay in a flow state, while 87% reported preserving mental effort during repetitive tasks. The tools eliminate tedium while amplifying human capabilities in design, architecture, and creative problem-solving.

A 2025 Yale Budget Lab study provides real-world evidence. Despite software developers being “in the top quintile of exposure” to AI tools and adopting them “extremely quickly and at mass scale,” researchers found “no economy-wide employment disruption” 33 months after ChatGPT’s release. For software engineers specifically, the workers most exposed to AI, there has been no major job displacement. Zero. The study concludes that fears of AI “eroding the demand for cognitive labor across the economy” are unfounded.

Translation: we’re fine. Again.

Software engineering involves what researchers call “tacit knowledge that’s difficult to verbalize”—intuitive understanding of system behavior, pattern recognition across contexts, architectural decision-making based on experience. This isn’t code generation. It’s a translation between human intent and digital reality.

Software engineering sits at the intersection of human needs and mathematical precision. This intersection requires translation skills that remain uniquely human. Every tool that facilitates translation doesn’t render translators obsolete but rather expands what can be translated, generating new requirements. Looking ahead, history suggests that current AI tools will find their place alongside compilers, debuggers, and IDEs — powerful amplifiers of human capability, not replacements for human judgment. Just like everything that came before.

The next breakthrough will likely promise, once again, to finally eliminate software engineers. And once again, it will create new opportunities for those who master both the tools and the irreducibly human aspects of software engineering.

The eternal promise of replacing software engineers remains just that — eternal and unfulfilled. Seven decades and counting.

I’m okay with that. Actually, I’m more than okay with it.

Seven decades of failed predictions have taught us something profound: software engineering has never been about the code itself. Code is merely a medium for communicating intent to computers. We went from punch cards to assembly language, from COBOL to Python, and now to natural language prompts. Each evolution changes how we express ourselves, but the fundamental challenge remains unchanged: understanding what to build, why it matters, and how to translate human needs into software that works.

The artifact, the running application that solves real problems, is what matters. Whether we get there through assembly instructions, high-level code, or AI-assisted prompts is secondary. The medium changes. The work doesn’t.

We will continue to see innovative ways of people communicating with computers. The tools will get better. The abstractions will get higher. The predictions will get louder. But the cognitive work of software engineering, the problem-solving, the architectural thinking, the bridging of human intention and digital reality, that’s not going anywhere.

Twenty years in, I’ve learned to stop worrying about the predictions and focus on the patterns. The patterns don’t lie.

This time isn’t different. It never is.