Listen to this article (AI-generated narration)

I recently came across Adia Sowho’s article “Tomorrow’s Growth Starts with Today’s Code”, and it resonated deeply. She has been at the forefront of Africa’s tech renaissance, building and scaling systems that serve millions across multiple continents. Her article isn’t just another think piece, it’s a battle-tested playbook from someone who’s seen what happens when startups hit hypergrowth without the right foundations.

If you’ve ever worked in emerging markets, dealing with 2G connections, multiple currencies, USSD interfaces, and mobile apps all at once, you’ll recognize these patterns. You’ve probably discovered them the hard way, during those 2 AM firefighting sessions. But for those starting out, translating these high-level concepts into code that works across diverse markets can be overwhelming.

What follows is everything I wish I knew when I was starting out, real code, patterns, and lessons from experience.

The Ten Principles

- API-First Design - Building tomorrow’s platform today

- Feature Flags - The emergency brake that saves deals

- Rules Engines - When business teams stop waiting for engineering

- Schema-Driven Design - Building forms that adapt to reality

- Event-Driven Architecture - Adding features without breaking everything

- Separation of Concerns - When marketing can move without breaking engineering

- Domain-Driven Design - Speaking the same language

- Infrastructure as Code - Scaling without manual bottlenecks

- Modular Architecture - Teams that don’t step on each other

- Observability by Default - Knowing what happened before anyone asks

Let’s look at each one in detail.

Principle 1 - API-First Design: Building Tomorrow’s Platform Today

Every core function should be designed as an API, even if it’s initially for internal use.

— Adia Sowho

The power of API-first design is how it prepares you for opportunities you can’t yet see. That payment system you’re building today might power your web app now, but next quarter it could enable a partner integration, support a mobile app, or even work with USSD for feature phones.

When you treat every feature as an API from the start, you create natural boundaries and clear contracts. Each endpoint becomes a promise about what your system does. These promises become the foundation of trust between your services and everyone who depends on them.

Think of it this way: APIs are products, and their consumers are your customers. Whether those customers are your own frontend, mobile apps, or external partners, they all deserve the same level of reliability and thoughtfulness.

Here’s how to build that foundation:

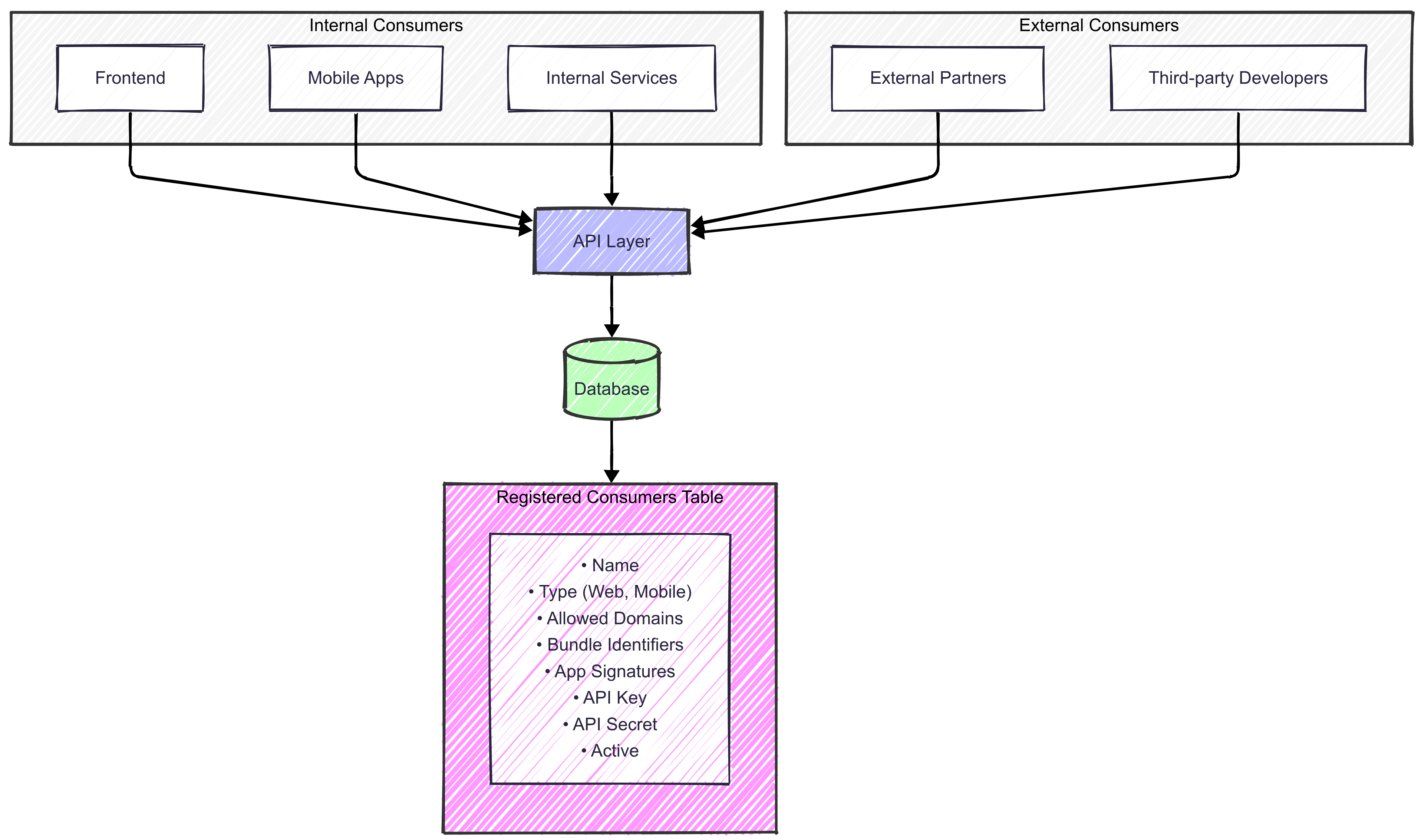

API-first architecture with a central API layer serving all consumers - web, mobile, USSD, and third-party integrations.

API-first architecture with a central API layer serving all consumers - web, mobile, USSD, and third-party integrations.

Living Documentation

You know that feeling when you’re trying to integrate with an API and the documentation is out of date? Or worse, it doesn’t exist? That’s what happens when documentation is treated as a separate task. The solution is surprisingly simple: make your documentation part of your code.

Start with an OpenAPI specification before writing any implementation. This single file becomes your contract, your documentation, and your test suite all at once. Tools like Committee (Ruby), openapi-backend (Node), or Schemathesis (Python) validate every response against your spec. When implementation drifts from documentation, tests fail immediately.

Here’s what this looks like for a payment processing API:

# api_spec.yaml

openapi: 3.0.0

paths:

/v1/payments:

post:

summary: Create a payment

requestBody:

required: true

content:

application/json:

schema:

type: object

required: [amount, currency, customer_id]

properties:

amount:

type: integer

minimum: 1

currency:

type: string

enum: [NGN, KES, ZAR, GHS]

customer_id:

type: string

pattern: '^cust_[a-zA-Z0-9]+$'

responses:

200:

description: Payment processed successfully

400:

description: Invalid request parameters

429:

description: Rate limit exceeded

headers:

X-RateLimit-Remaining:

description: Requests remaining

# spec/api/payments_spec.rb

RSpec.describe 'Payments API' do

it 'creates a payment with valid data' do

post '/v1/payments',

params: { amount: 5000, currency: 'NGN', customer_id: 'cust_8274' },

headers: { 'X-API-Key' => api_key }

expect(response).to have_http_status(200)

assert_response_schema_confirm(200) # Validates against OpenAPI spec

end

it 'enforces rate limits' do

101.times { post '/v1/payments', params: valid_params, headers: auth_headers }

expect(response).to have_http_status(429)

expect(response.headers).to include('X-RateLimit-Remaining')

end

end

This specification-driven approach gives you:

- Living documentation: Tests validate against the spec on every run

- Auto-generated tools: Create SDKs, Postman collections, and mock servers from one source

- Contract enforcement: Changes to API behavior fail tests immediately

- Developer confidence: Every example in your docs comes from actual test runs

Authentication

Here’s something that’s easy to overlook: the internal API you’re building today might become a partner integration tomorrow. Building authentication in from the start isn’t paranoia. It’s preparation for success.

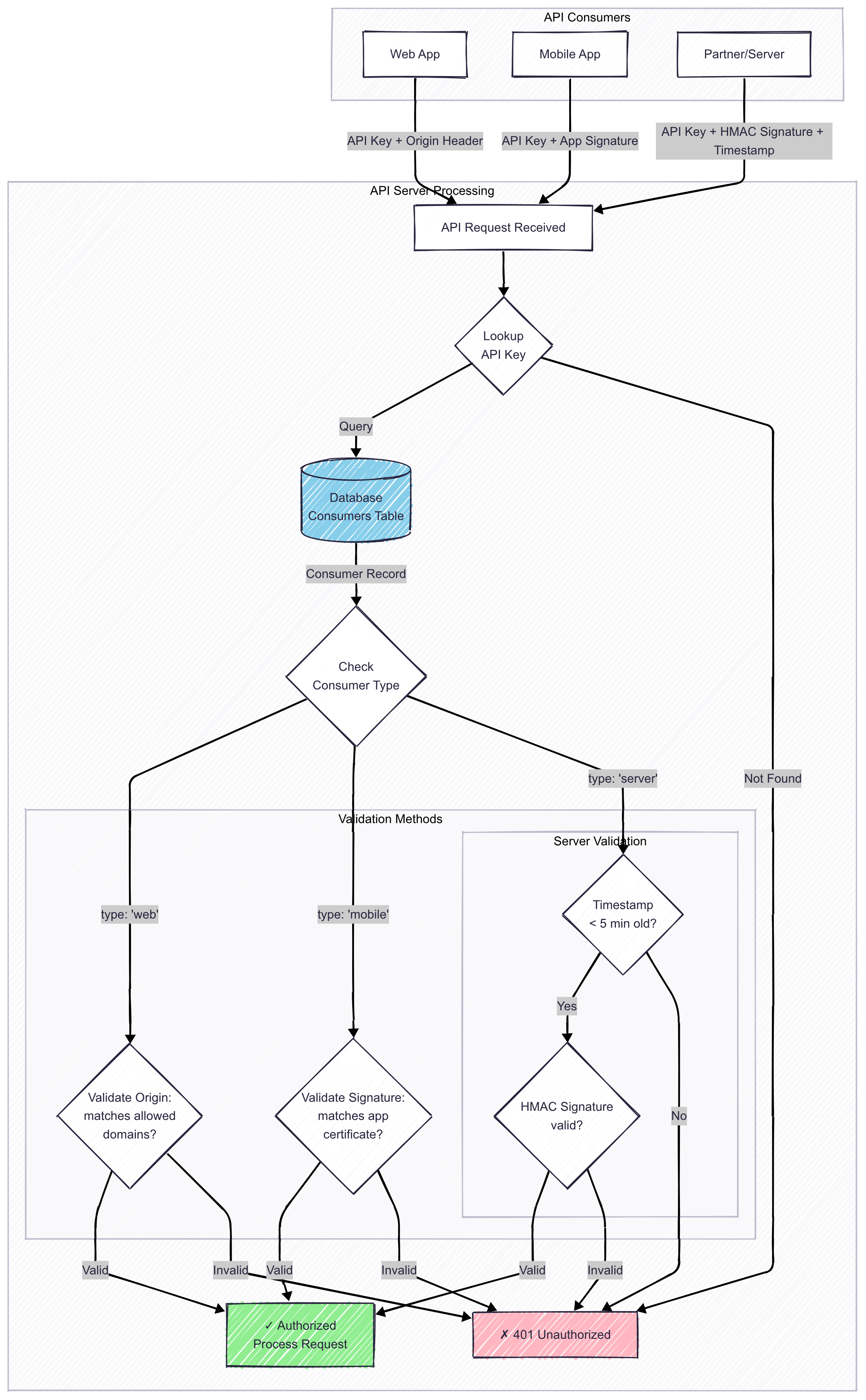

Multi-layered API authentication strategy showing different security approaches for web, mobile, and server-to-server communications.

Multi-layered API authentication strategy showing different security approaches for web, mobile, and server-to-server communications.

For public-facing apps (web/mobile):

- Use API keys for identification plus origin validation

- Web apps: Validate the Origin header against your whitelist (browsers enforce this strictly)

- Mobile apps: Require app signatures, cryptographic hashes the OS generates from your signing certificate

For server-to-server communication:

- Implement request signing with HMAC-SHA256

- Include method, path, body, and timestamp in the signature

- This prevents replay attacks and proves the request hasn’t been tampered with

Error Handling

The difference between a good API and a great one often comes down to how it handles failure. Things will inevitably go wrong. Networks timeout, validation fails, rate limits get hit. When they do, your error messages become the roadmap that helps developers find their way back to success.

Error Format

Every error response should follow this structure:

{

"error": {

"code": "VALIDATION_FAILED",

"message": "The request contains invalid data",

"request_id": "req_8n3mN9pQ2x",

"details": {

"amount": "Must be greater than 0",

"currency": "USD is not supported for this merchant"

}

}

}

Every field serves a purpose:

code: A constant for programmatic handlingmessage: Human-readable text for end usersrequest_id: Your debugging lifelinedetails: Field-specific errors for bulk fixes

This structure scales from validation errors to distributed system failures.

Status Codes

Stick to standard HTTP status codes. They’re not just convention, they’re contracts. A 503 tells load balancers to try another server. A 429 triggers backoff algorithms. A 304 enables caching. Return 200 for errors and you break everything: CDNs cache your error pages, monitoring thinks you’re healthy, client libraries retry the wrong things. The entire internet infrastructure expects these codes to mean what they say.

Error Codes

Beyond HTTP status codes, create consistent error codes for your specific domain (like PAYMENT_FAILED, INSUFFICIENT_BALANCE, DUPLICATE_ORDER). The exact codes don’t matter as much as being consistent. Pick a convention and stick to it. Developers need to know that PAYMENT_FAILED always means the same thing, whether it shows up today or six months from now.

Request IDs

Generate a unique request ID for every API call:

req_8n3mN9pQ2x // prefix + random string

Include this ID in every response and log it with full context. When a developer reports an issue with req_8n3mN9pQ2x, you jump straight to the exact request, see what went wrong, and often fix it before they finish typing their support ticket.

This transforms debugging from archaeological expeditions into surgical strikes. With that ID, you pull up everything: what they sent, how long it took, what broke. No more scrolling through logs trying to piece together what happened. The request ID is your breadcrumb trail back to the exact moment things went sideways.

Validation Errors

For validation errors, provide field-level details:

{

"error": {

"code": "VALIDATION_FAILED",

"message": "The request contains 3 validation errors",

"request_id": "req_8n3mN9pQ2x",

"details": {

"amount": "Must be between 50 and 999999",

"customer_id": "Customer cust_xyz not found",

"currency": "JPY is not enabled for your account"

}

}

}

This lets developers fix everything in one shot.

Security

Error messages should never leak sensitive information about your system. Handle errors securely like this:

| Instead of | Use |

|---|---|

PostgreSQL error: relation 'users' does not exist | An internal error occurred. Please contact support with request ID req_8n3mN9pQ2x |

User not found vs Incorrect password | Invalid credentials (same message for both cases) |

Connection to database server at 192.168.1.100 failed | Service temporarily unavailable |

Invalid token: signature expired at 2024-01-15 14:23:45 | Authentication failed. Please obtain a new token |

Logging

Log enough context to reconstruct what happened:

| Component | Details |

|---|---|

| Request Context | Request ID, timestamp, duration |

| API Consumer | Who made the request, API key/client ID |

| Request Details | Endpoint, HTTP method, response code |

| Request Body | Sanitized request body (remove sensitive data) |

| Error Information | Full error details and stack trace (for 500 errors) |

| Business Context | Any relevant domain-specific information |

Actionable Errors

Good error messages tell developers how to fix the problem:

| Error Type | Actionable Message |

|---|---|

| Rate Limiting | “Rate limit exceeded. Limit resets at 2024-01-15T14:00:00Z” |

| Validation | “Amount must be between 100 and 10000000 kobo” |

| Configuration | “Currency USD is not enabled. Supported currencies: NGN, KES, ZAR, GHS” |

| Business Rules | “BVN validation required for transactions above ₦50,000” |

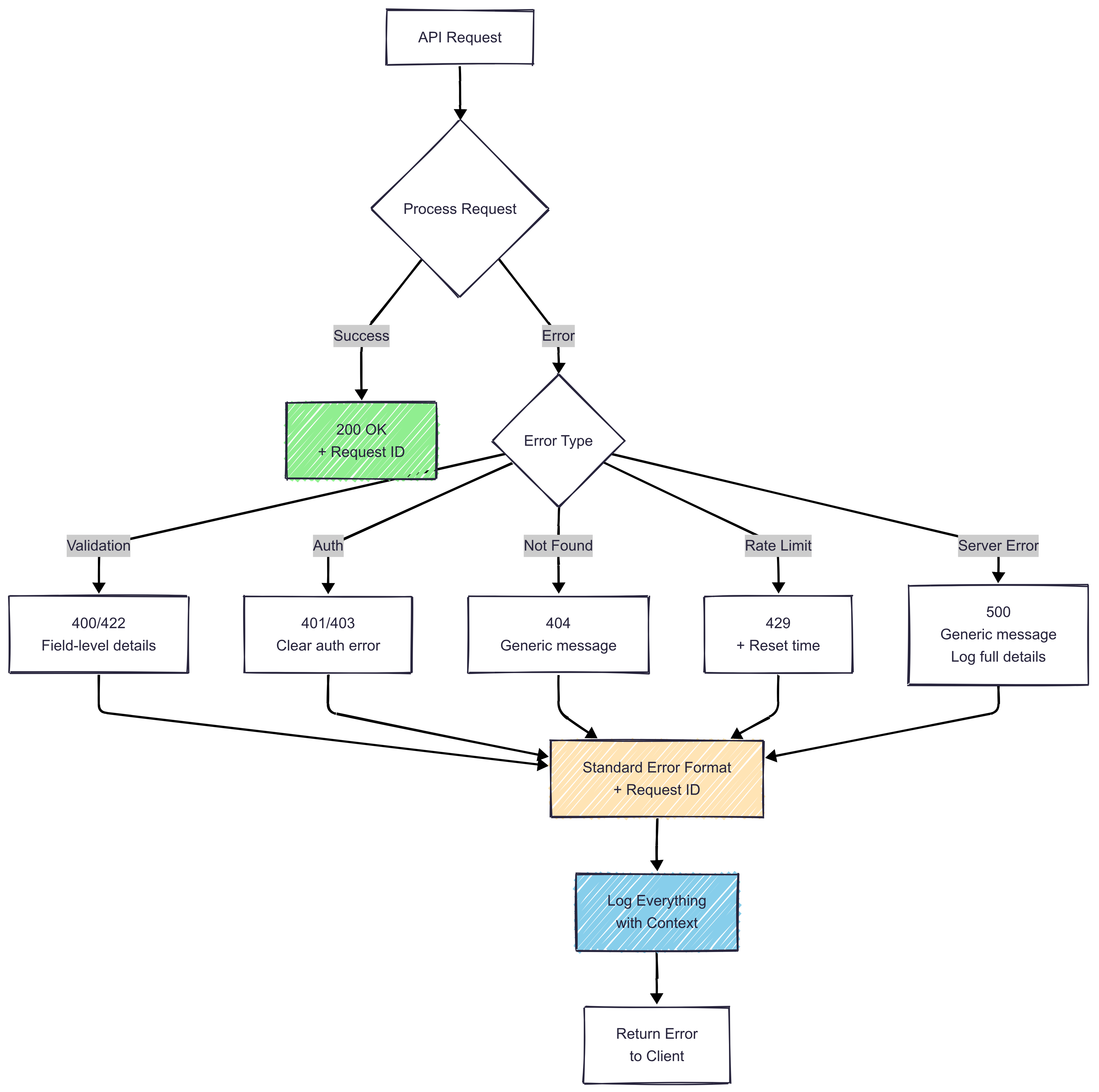

Comprehensive error handling flow with structured error responses, request IDs for debugging, and actionable error messages.

Comprehensive error handling flow with structured error responses, request IDs for debugging, and actionable error messages.

Actionable errors reduce support tickets and improve developer experience.

Versioning

Let’s address the elephant in the room: your API will change. That’s not a failure of planning, but a sign of growth. New requirements emerge, better patterns become clear, and sometimes you just learn that your initial design had flaws. Versioning is how you evolve without leaving anyone behind.

URL Versioning

After trying headers, query parameters, and content negotiation, URL versioning remains the clearest approach:

https://api.yourcompany.com/v1/payments

https://api.yourcompany.com/v2/payments

The version is immediately visible in logs, curl commands, and browser history. When developers see /v1/, they instantly know there might be newer versions to explore. No guessing, no hidden complexity.

You need v2 when you:

- Remove an endpoint or field (even if “nobody uses it”)

- Change a field’s type (that string ID becoming a number)

- Add required parameters to existing endpoints

- Change what a field means (active: true now means something different)

- Modify error response formats

- Switch authentication methods

You DON’T need v2 when you:

- Add new endpoints (v1 just got richer)

- Add optional parameters (backward compatible)

- Add fields to responses (clients ignore what they don’t expect)

- Fix bugs (unless someone’s workflow depends on that bug)

- Improve performance (invisible to consumers)

Granular Versioning

Versioning everything at once forces full rewrites for every integration.

Version by endpoint instead:

https://api.yourcompany.com/v1/customers (unchanged, still v1)

https://api.yourcompany.com/v2/payments (breaking changes here)

https://api.yourcompany.com/v1/invoices (unchanged, still v1)

When v1 and v2 need different data shapes:

- Add columns, never modify existing ones

- Use database views for version-specific representations

- Transform at the API layer, not the database

- Keep v1 columns until v1 is completely dead (not just deprecated)

Common Mistakes

| Mistake | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| The “Quick Fix” Trap | “Just a tiny breaking change to v1, nobody will notice.” | They notice. They always notice. And they remember. |

| The Silent Deprecation | Surprising developers with sunset dates | This is how you lose customers. Communicate early, communicate often. |

| The Premature V2 | Creating v2 just because you learned something new | Version 17 of your API isn’t a good look. Batch breaking changes together. |

| The Impossible Migration | Moving from v1 to v2 requires rewriting everything | You’ve created a new API, not a new version. |

Start with /v1/ in your URLs today, even if you’re convinced your API is perfect. Future you will thank present you when that breaking change request lands on your desk.

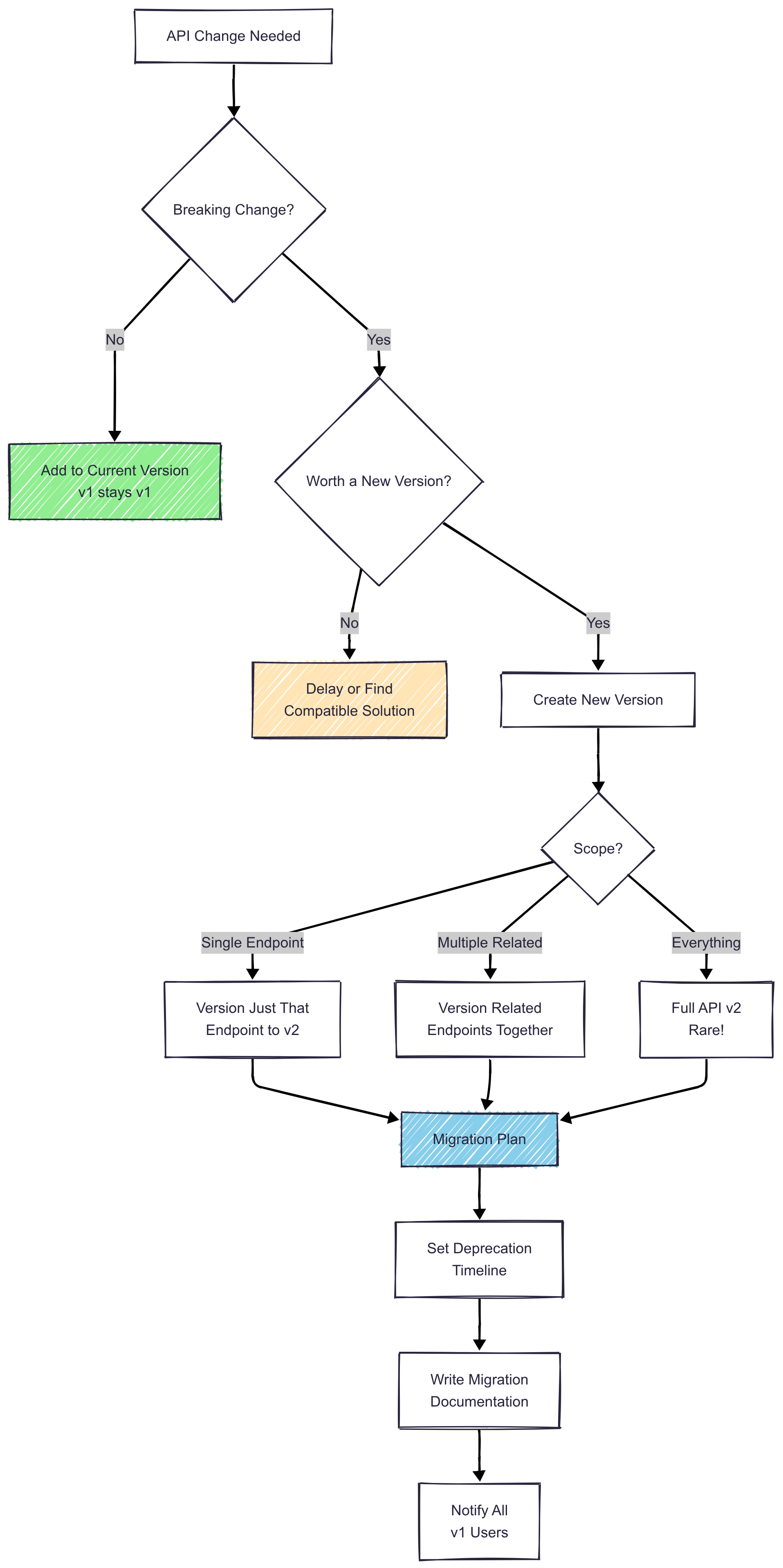

API versioning decision tree helping determine when breaking changes require a new version versus when changes can be backward compatible.

API versioning decision tree helping determine when breaking changes require a new version versus when changes can be backward compatible.

Versioning embraces the reality that your API will grow and change, just like your business.

Rate Limiting

Here’s a scary truth: one misconfigured React hook can take down your entire API. A missing dependency array triggers infinite requests. A retry loop during network issues becomes a self-inflicted DDoS attack. Rate limiting is your safety net that keeps mistakes from becoming disasters.

Redis Solution

The good news? You don’t need complex distributed systems to get started. This simple Redis-based approach handles 99% of use cases:

For each request, create a Redis key that combines the API key and current hour:

rate_limit:api_key_xyz:2024-01-15-14

Increment the counter, set it to expire in one hour, check if it exceeds your limit. That’s it. Ten lines of code that will save your startup one day:

# app/services/rate_limiter.rb

def check_rate_limit(api_key)

key = "rate_limit:#{api_key}:#{Time.now.strftime('%Y-%m-%d-%H')}"

count = redis.incr(key)

redis.expire(key, 3600) if count == 1

{ allowed: count <= 1000, remaining: [1000 - count, 0].max }

end

This sliding window approach handles all the edge cases. No complex math, no drift, just reliable protection.

Shared API Keys

If your frontend app serving thousands of users uses API key web_abc123, every single user shares that same rate limit. Set it to 1000 requests/hour and one user with unstable internet retrying requests locks out your entire customer base. You’ve just DDoS’d yourself.

Multi-Level Defense

For public-facing apps, you need defense in depth. Think of it like a bouncer, a velvet rope, and a capacity limit all working together:

Level 1: Per API Key (The Capacity Limit)

10,000 requests/hour for the entire app

Key: rate_limit:web_abc123:2024-01-15-14

Last line of defense. If your frontend has bugs, the bleeding stops here.

Level 2: Per IP Address (The Velvet Rope)

1,000 requests/hour per IP + API key combo

Key: rate_limit:web_abc123:ip:192.168.1.1:2024-01-15-14

Stops individual bad actors without punishing everyone else.

Level 3: Per User (The Bouncer)

500 requests/hour per user + API key combo

Key: rate_limit:web_abc123:user:user_123:2024-01-15-14

Most accurate but requires authentication. Perfect for logged-in sections.

Check limits from most specific to least specific:

# app/services/multi_level_rate_limiter.rb

def check_multi_level_limits(api_key, ip, user_id = nil)

hour = Time.now.strftime('%Y-%m-%d-%H')

# Check limits from most specific to least specific

limits = [

user_id && ["rate_limit:#{api_key}:user:#{user_id}:#{hour}", 500],

["rate_limit:#{api_key}:ip:#{ip}:#{hour}", 1000],

["rate_limit:#{api_key}:#{hour}", 10000]

].compact

limits.each do |key, limit|

result = check_limit(key, limit)

return result unless result[:allowed]

end

end

Rate Limit Headers

Rate limit headers should tell users which limit they hit:

X-RateLimit-Limit: 1000

X-RateLimit-Remaining: 45

X-RateLimit-Reset: 1705320000

X-RateLimit-Resource: ip // The specific limit they're hitting

For 429 errors, add:

Retry-After: 3600

Turns vague frustration into actionable information.

Real-World Limits

Endpoints have different costs. Health checks cost nothing. Complex searches hit multiple database tables.

By Operation Type:

- Standard endpoints: 1000 requests/hour (normal CRUD operations)

- Expensive operations: 100 requests/hour (search, analytics, bulk operations)

- Auth endpoints: 20 attempts/hour (prevent brute force attacks)

By Consumer Type:

- Server-to-server: 10,000/hour per API key (they can handle retries)

- Web app total: 50,000/hour per API key (all your users combined)

- Web app per IP: 1,000/hour (stops individual abuse)

- Mobile app total: 100,000/hour per API key (mobile users are clickier)

- Mobile app per device: 2,000/hour (higher than web because no shared IPs)

Start conservative, then adjust based on usage patterns.

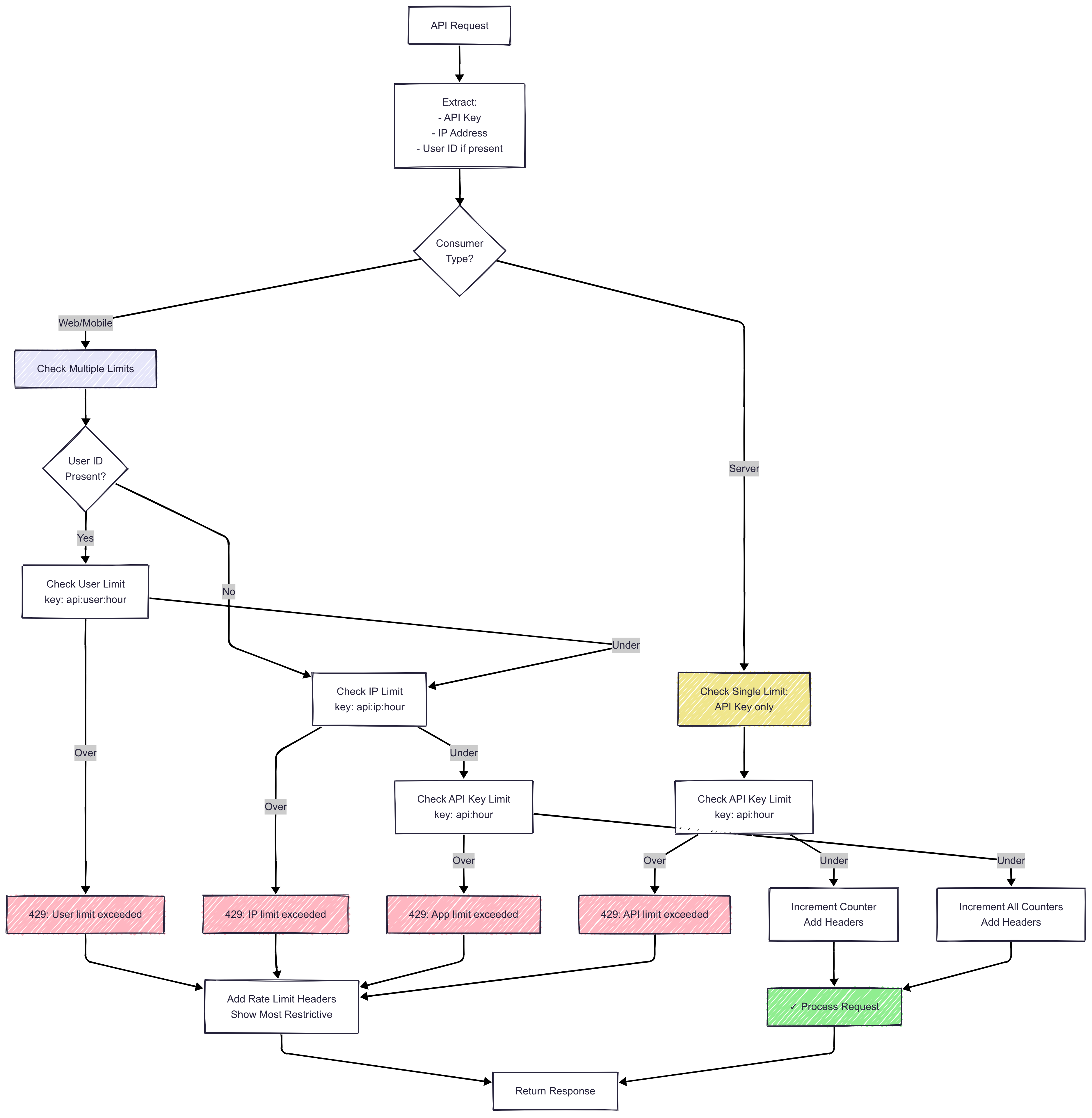

Multi-level rate limiting architecture with per-API-key, per-IP, and per-user limits to prevent abuse while maintaining good user experience.

Multi-level rate limiting architecture with per-API-key, per-IP, and per-user limits to prevent abuse while maintaining good user experience.

Rate limiting done right is invisible to good actors and impenetrable to bad ones.

Idempotency

Picture this nightmare scenario: Payment goes through. Network drops the response. Client retries. Customer gets charged twice. This happens more often than you’d think, especially with mobile networks and flaky connections. Idempotency is your protection against these inevitable network failures.

Simple Solution

The solution is elegantly simple: let clients include a unique Idempotency-Key header. When you see that key again, return the original response instead of reprocessing:

# app/services/payment_processor.rb

def process_payment(request, idempotency_key)

# Check if we've seen this key before

existing = IdempotentRequest.find_by(key: idempotency_key)

return existing.response if existing

# Process and store the result

result = actually_process_payment(request)

IdempotentRequest.create!(

key: idempotency_key,

response: result,

expires_at: 48.hours.from_now

)

result

end

When to Use It

GET requests are naturally idempotent. But when you’re moving money, creating orders, or sending notifications, idempotency isn’t optional.

Always use idempotency for:

- Payment processing (obviously)

- Order creation

- Subscription changes

- Money transfers

- Refunds and credits

- Sending emails/SMS (nobody wants duplicate “Your order has shipped!” emails)

- Any operation that costs real money

Skip it for:

- GET requests (already idempotent)

- Search operations

- Authentication endpoints

- Analytics events (duplicates are usually fine)

Database Schema

A schema that handles real-world complexity:

CREATE TABLE idempotent_requests (

idempotency_key VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

api_consumer_id VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

request_hash VARCHAR(64),

response_body TEXT,

response_status INTEGER,

expires_at TIMESTAMP,

UNIQUE INDEX idx_key_consumer (idempotency_key, api_consumer_id)

);

Why include api_consumer_id? Because different clients might accidentally generate the same UUID. The request hash? To catch when someone reuses a key with different parameters (spoiler: that’s always a bug).

Good idempotency keys:

- UUIDs:

550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000 - Request-specific:

order-12345-attempt-1 - Hash of critical params:

sha256(user_id + amount + timestamp)

Keys to avoid:

- User ID (what about their second payment?)

- Current date (everyone paying at midnight gets merged)

- Sequential numbers (hello race conditions)

Keys should represent the user’s intent. Creating the same order? Same key. Creating a different order? Different key.

Edge Cases

Still Processing: When a duplicate request arrives while the first is still running, return 409 Conflict:

{

"error": {

"code": "STILL_PROCESSING",

"message": "Request with this idempotency key is still being processed",

"retry_after": 5

}

}

Changed Request: When someone reuses a key with different parameters, return 422 Unprocessable Entity:

{

"error": {

"code": "IDEMPOTENCY_KEY_REUSED",

"message": "This idempotency key was used with different request parameters"

}

}

Client Implementation

SDKs should handle idempotency automatically:

// src/api/payment-client.ts

// Bad - client manages keys manually

api.createPayment(amount, { idempotencyKey: 'payment-123' })

// Good - SDK generates and manages keys

api.createPayment(amount) // SDK handles idempotency internally

Educate through documentation:

- Generate a new key for each distinct business operation

- Save the key until you get a definitive response

- On timeout/network error, retry with the same key

- On client error (4xx), fix the request and use a new key

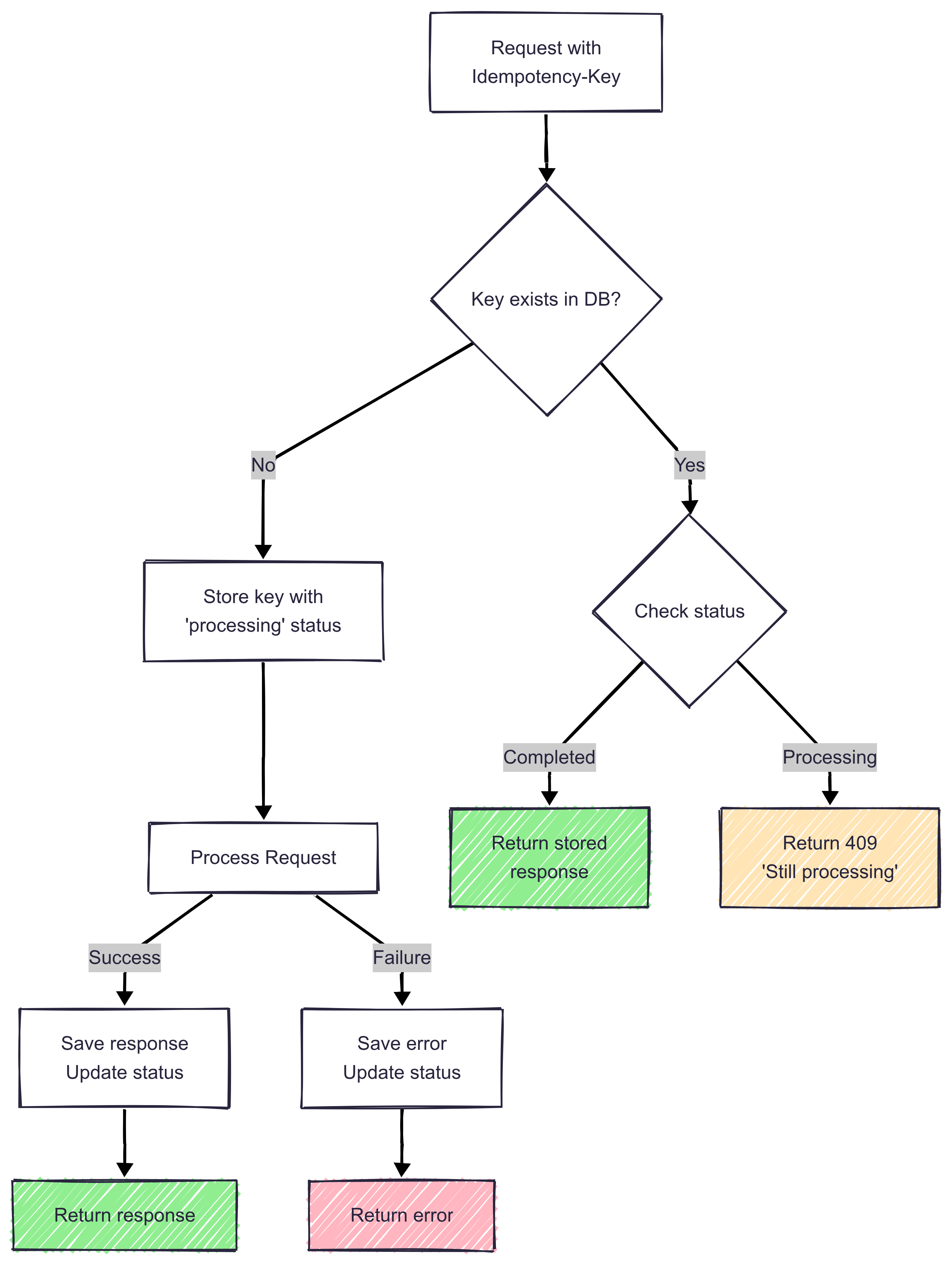

Idempotency implementation flow showing how duplicate requests are handled safely, preventing issues like double charges during network failures.

Idempotency implementation flow showing how duplicate requests are handled safely, preventing issues like double charges during network failures.

The Cultural Shift

API-first thinking changes how teams approach every feature. Instead of asking “How do we build this for our app?”, teams ask “How do we expose this capability to any consumer?”

This shift manifests in daily practices: frontend developers mock against API contracts before backend is ready. Product managers think in terms of capabilities, not screens. QA tests API contracts, not just UI flows. Documentation becomes a first-class deliverable, not an afterthought.

The transformation is complete when your mobile developer can build a feature without asking backend for changes, your partner can integrate without meetings, and your support team can answer integration questions by sharing OpenAPI docs. That’s when you know you’ve truly become API-first.

Principle 2 - Feature Flags: The Emergency Brake That Saves Deals

Wrap every major new feature in a toggle, so you can turn it on or off without shipping new code.

— Adia Sowho

The power of feature flags becomes clear the first time you need them. Picture this: your new recommendation engine is live, but showing competitor products to your users. With feature flags, you turn it off in seconds. Without them, you’re rushing a hotfix through deployment while customers screenshot your mistakes.

But feature flags are more than emergency switches. They’re sophisticated access control systems that answer questions like: Who sees this feature? On which platforms? At what pricing tier? During which time periods?

The Four Layers

Here’s the key insight about feature flags: access control requires multiple layers of defense. Think of it like airport security - you don’t rely on just one checkpoint. A bug in your mobile app shouldn’t give free users access to enterprise features. You need granular control because you can’t force all users to update immediately, and you can’t disable features globally without affecting paying customers.

Four-layer feature flags architecture providing granular control from global kill switches to individual user permissions.

Four-layer feature flags architecture providing granular control from global kill switches to individual user permissions.

Multiple checkpoints: feature enabled, consumer authorized, account plan, user permissions. Fail any check, access denied.

Layer 1: Global Kill Switch

Emergency brake. When a critical service starts misbehaving in production, flip this switch instantly.

features:

bulk_export: enabled

ai_insights: disabled # "Coming January 2025"

advanced_analytics: maintenance # "Under maintenance"

Layer 2: Platform Guard

Saves you when iOS apps are stuck in review and Android apps have version-specific bugs.

# Platform-specific configuration

ios_app_v2.1:

bulk_export: enabled

ai_insights: disabled # Waiting for adoption

android_app_v2.0:

bulk_export: disabled # Version can't handle it

new_upload_flow: disabled

Layer 3: Business Model

This is where your pricing tiers meet reality. That enterprise customer who negotiated unlimited API calls? The startup on the free tier who’s somehow using 90% of your resources? This layer handles all of that.

# Account-based feature configuration

enterprise:

bulk_export: { enabled: true, limit: unlimited }

ai_insights: { enabled: true, quota: 10000/month }

white_label: true

free_tier:

bulk_export: { enabled: true, limit: 10/month }

ai_insights: false

white_label: false

Layer 4: Permissions

The finest grain of control. Not everyone in a company should be able to export all customer data or change billing settings.

# Role-based permissions

admin: [bulk_export.*, ai_insights.*, billing.*]

analyst: [bulk_export.execute, ai_insights.view]

intern: [ai_insights.view]

Making It Work

Notice how this builds on our API-first foundation? Each of these layers maps perfectly to API concepts we’ve already established. Consumer validation builds on authentication patterns. Account plans connect to rate limiting. Permissions integrate with request context.

With this elegantly simple system, every request flows through all four gates:

# app/services/feature_access.rb

def can_access?(feature, user, consumer, action = :use)

# Check all four layers in sequence

feature_enabled?(feature) &&

consumer_has_feature?(consumer, feature) &&

account_has_feature?(user.account, feature) &&

user_can?(user, "#{feature}.#{action}")

end

Implementation Details

Cache Everything, But Smartly

# app/services/feature_cache.rb

def cache_key(user, feature, consumer)

"access:#{feature}:#{consumer}:#{user.account_id}:#{user.role}"

end

Rails.cache.fetch(cache_key, expires_in: 5.minutes) do

can_access?(feature, user, consumer)

end

Make It Observable

{

"event": "access_denied",

"feature": "bulk_export",

"reason": "account_limit_exceeded",

"details": {

"layer_failed": 3,

"account_limit": 100,

"current_usage": 100,

"user_id": "usr_123",

"consumer": "web_app"

}

}

Build a Control Panel for Visibility

Feature: AI Insights

├─ Status: 🟢 Enabled

├─ Consumers:

│ ├─ Web: 🟢 100%

│ ├─ iOS 2.1: 🟡 50% (rolling out)

│ ├─ iOS 2.0: 🔴 Disabled (force update)

│ └─ Android: 🟢 100%

├─ Plans:

│ ├─ Free: 3 uses/month

│ ├─ Pro: 100 uses/month

│ └─ Enterprise: Unlimited

└─ Roles:

├─ Admin: Full

├─ User: Read-only

└─ Guest: None

The Cultural Shift

Feature flags transform deployment from a high-stakes event to a routine operation. Teams ship code daily knowing they can instantly disable problematic features. Product managers run A/B tests without engineering involvement. Sales can enable premium features during demos without special builds.

The mindset shifts from “Is this ready to ship?” to “Is this ready to test in production?” Developers become comfortable with incomplete features in main branches. Operations teams sleep better knowing they have kill switches. Customer success can resolve issues without escalation.

When feature flags become second nature, innovation accelerates. Teams experiment freely because failure is reversible. That’s the real power - not just controlling features, but removing the fear of shipping.

Principle 3 - Rules Engines: When Business Teams Stop Waiting for Engineering

Complex logic (pricing, eligibility, workflows, even site color schemes) should live in configurable rule-based engines, not buried in code.

— Adia Sowho

Think about how often business rules change. New pricing models, seasonal discounts, regional compliance requirements, special customer agreements. When these rules are hardcoded, every change becomes a development cycle. A simple “20% off for the holidays” turns into a two-week sprint.

Rule-based engines solve this by separating what the business wants from how the code works. Your business teams can configure rules directly, not through complex enterprise software that requires consultants, but through simple, understandable interfaces that give them control without causing problems.

The Layered Architecture

Here’s how I think about rules engines: business rules form a hierarchy similar to government laws. You have global policies at the top, then regional requirements, customer agreements, and temporary overrides. Each layer cascades from general to specific, with the ability to override or refine the rules above it.

This creates a system that’s both consistent and flexible. But the magic is in the details.

Layer 1: System Rules

Bedrock principles that apply unless explicitly overridden:

system_rules:

shipping: { standard: 9.99, express: 19.99, free_threshold: 100 }

pricing: { min_margin: 0.15, max_discount: 0.30 }

fraud: { max_first_order: 500, velocity_limit: 5/day }

Layer 2: Regional Rules

Different markets have different regulations, payment methods, compliance requirements, and data residency laws.

regional_rules:

region_a:

payments: { methods: [bank, card], vat: 0.075, kyc: true }

region_b:

payments: { methods: [mobile_money, card], vat: 0.16 }

delivery: { cod: true, express: true }

Layer 3: Segment Rules

Where your business model lives. Enterprise customers get different treatment. Marketplace sellers have different fees. Premium subscribers get exclusive perks.

segment_rules:

enterprise:

volume_discounts: { 100: 0.10, 1000: 0.20 }

payment_terms: net_60

marketplace:

fees: { transaction: 0.029, listing: 0.20 }

payout: daily

Layer 4: Account Rules

Some customers’ needs, like those of early believers, high volume accounts, major enterprise accounts, high-referral partners, must be prioritized. They usually have custom contracts or special arrangements with the company.

account_rules:

major_enterprise:

pricing: { discount: 0.25, free_shipping: true }

support: { sla: 4h, dedicated_rep: true }

Layer 5: Temporal Rules

Handle time-bound promotions and seasonal variations without permanent business logic changes.

temporal_rules:

holiday_sale:

active: "2024-12-15 to 2024-12-31"

discount: 0.20

flash_deals: { electronics: 0.30, midnight: +0.10 }

shipping: { free_threshold: 25 }

Making Layers Work

Rules cascade through layers of organizational hierarchy. Each layer gets a vote, and you decide how conflicts resolve. In practice:

# app/services/shipping_calculator.rb

def calculate_shipping(order, customer)

# Cascade through all rule layers

rate = apply_rules_cascade([

system_rules.shipping,

regional_rules[order.region],

segment_rules[customer.segment],

account_rules[customer.id],

active_temporal_rules

])

order.total >= rate.threshold ? 0 : rate.amount

end

Notice how each layer builds on the previous one? This isn’t a mess of if-else statements, but a clear progression from general to specific. When something goes wrong, you can trace exactly which layer made which decision.

Real-World Example

Let’s see how multiple rule layers combine for a specific transaction:

- System Rule: Base price ₦50,000, standard margin 20%

- Regional Rule: Local VAT of 7.5% applies

- Segment Rule: They’re a Gold customer (10% discount)

- Account Rule: Major distributor negotiated 15% discount (overrides segment)

- Temporal Rule: Detty December sale adds extra 5% off

The calculation flows naturally:

- Start with ₦50,000 base price

- Apply account discount: -₦7,500 (overrides the segment 10%)

- Apply Detty December sale: -₦2,125 (5% of ₦42,500)

- Subtotal: ₦40,375

- Add VAT: +₦3,028

- Final: ₦43,403

Managing Complexity

The difference between a rule-based engine that enables your business and one that cripples it comes down to three things: precedence, composition, and ownership.

Rule Precedence

precedence: [temporal, account, segment, regional, system]

conflict_resolution:

discounts: maximum

restrictions: most_restrictive

features: most_permissive

Rule Composition

Not all rules override, some combine:

rule_composition:

regional: additive

segment: multiplicative

account: replace

promotion: additive

Think of it like cooking. Some ingredients replace others (butter instead of oil), some multiply the effect (double the spice, double the heat), and some just add on top (extra cheese). Your rule-based engine needs to understand these relationships.

Rule Ownership

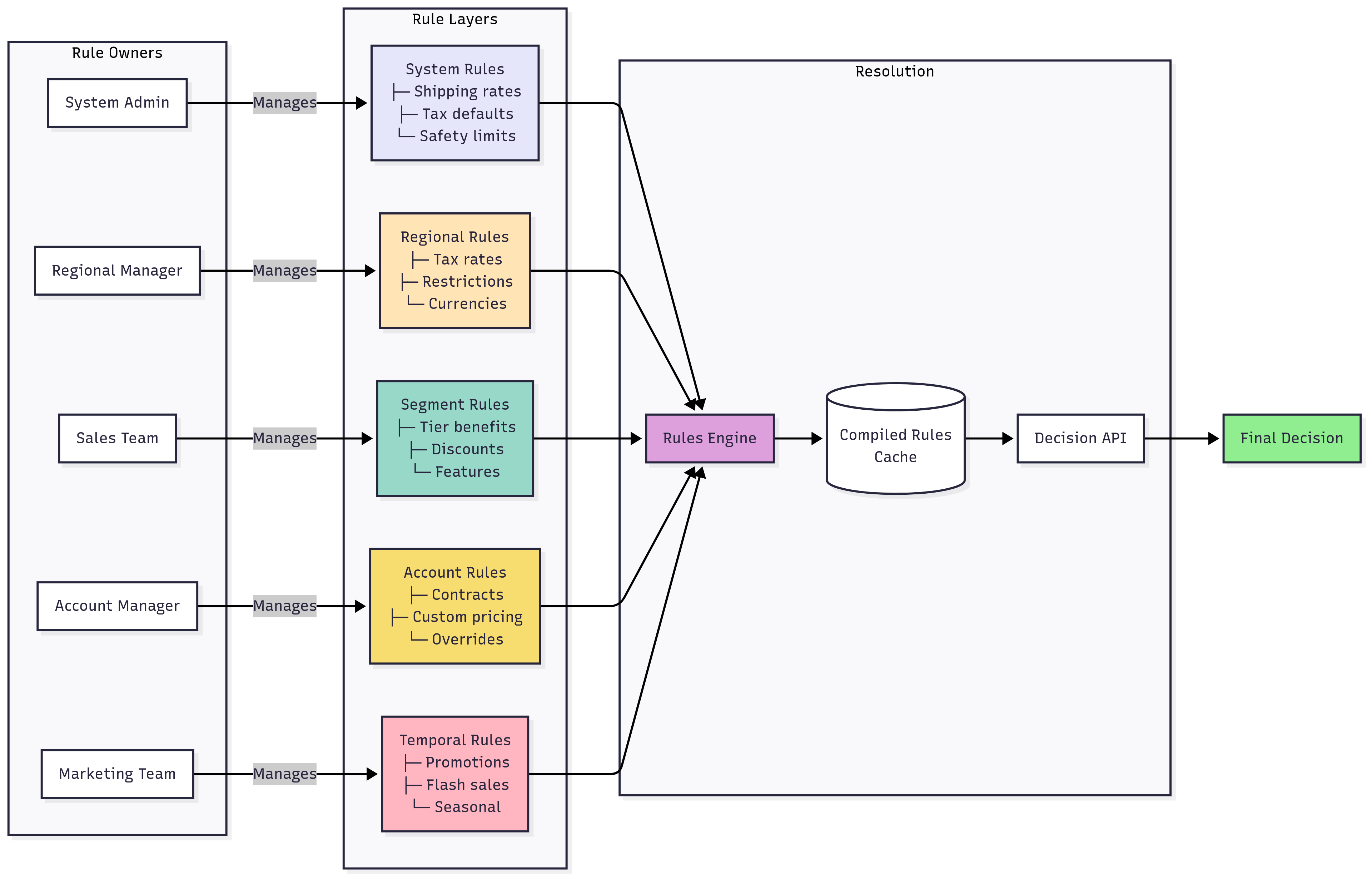

Hierarchical rule-based engine architecture showing how business rules cascade from global system rules to specific customer agreements.

Hierarchical rule-based engine architecture showing how business rules cascade from global system rules to specific customer agreements.

Migration Strategy

Migrating from existing code to a rule-based engine requires a careful approach:

Phase 1: Shadow Mode

Run the rule-based engine alongside existing code:

# app/services/price_calculator.rb

def calculate_price(order)

old_price = calculate_price_old_way(order)

new_price = RulesEngine.evaluate('pricing', order)

if (old_price - new_price).abs > 0.01

log_discrepancy(order, old_price, new_price)

end

old_price # Still use old calculation

end

You’re comparing results without affecting production. When discrepancies are near zero, you’re ready for phase 2.

Phase 2: Gradual Rollout

Start with your least risky layer:

# app/services/promotion_price_calculator.rb

def calculate_price(order)

# Use rule-based engine for promotions only

base_price = calculate_base_price_old_way(order)

promotional_discount = RulesEngine.evaluate('promotions', order)

base_price * (1 - promotional_discount)

end

Each week, move another piece to the rule-based engine. If something breaks, you’re only rolling back one layer, not everything.

Phase 3: Full Migration

Once everything’s in the rule-based engine, keep the old code around but deprecated:

# app/services/feature_flagged_price_calculator.rb

def calculate_price(order)

if Feature.enabled?(:rules_engine_pricing)

RulesEngine.evaluate('pricing', order)

else

calculate_price_old_way(order) # Emergency fallback

end

end

That feature flag is your insurance policy. When something goes wrong at 2 AM (and it will), you can flip back to the old system in seconds.

The Cultural Shift

The reality is that the hardest part of implementing a rule-based engine isn’t technical but organizational. Developers may feel like they’re losing control. Business teams may worry about taking on technical responsibilities. Everyone’s concerned about breaking something.

Start small and build trust. That regional manager who’s been begging for pricing flexibility? Give them control over their region’s shipping rules. When they successfully run a weekend promotion without engineering help, word spreads. Suddenly, everyone wants in.

The adoption pattern typically follows:

- Month 1: “This is too complicated, just hardcode it”

- Month 3: “Can we add our rules to the engine?”

- Month 6: “How did we ever live without this?”

Rule-based engines aren’t about taking power away from developers, they’re about giving power to the people who understand the business. When your head of sales can adjust pricing without a JIRA ticket, when your marketing team can launch campaigns without a deployment, when your regional managers can ensure compliance without a sprint, that’s when your business truly becomes agile.

Principle 4 - Schema-Driven Design: Building Forms That Adapt to Reality

Use metadata and schemas to define forms, tables, and data models rather than hardcoding them.

— Adia Sowho

Every market has its quirks. Nigeria needs BVN verification. Kenya requires KRA PINs. South Africa has different tax systems. When you’re expanding across markets, these requirements multiply fast. Before you know it, you’re maintaining dozens of slightly different forms, each with their own validation rules, database fields, and documentation.

The Problem

You’ve probably seen code like this:

// components/OnboardingForm.tsx - The hardcoded approach

function OnboardingForm({ country }) {

if (country === 'NG') {

return <form><input name="bvn" required />...</form>;

} else if (country === 'KE') {

return <form><input name="kra_pin" required />...</form>;

} // 500 lines of if-else statements...

}

Every new market requirement means updating this code. Adding a field means touching the form, the validation, the database, the API docs. One typo and customers in an entire country can’t sign up.

The Solution

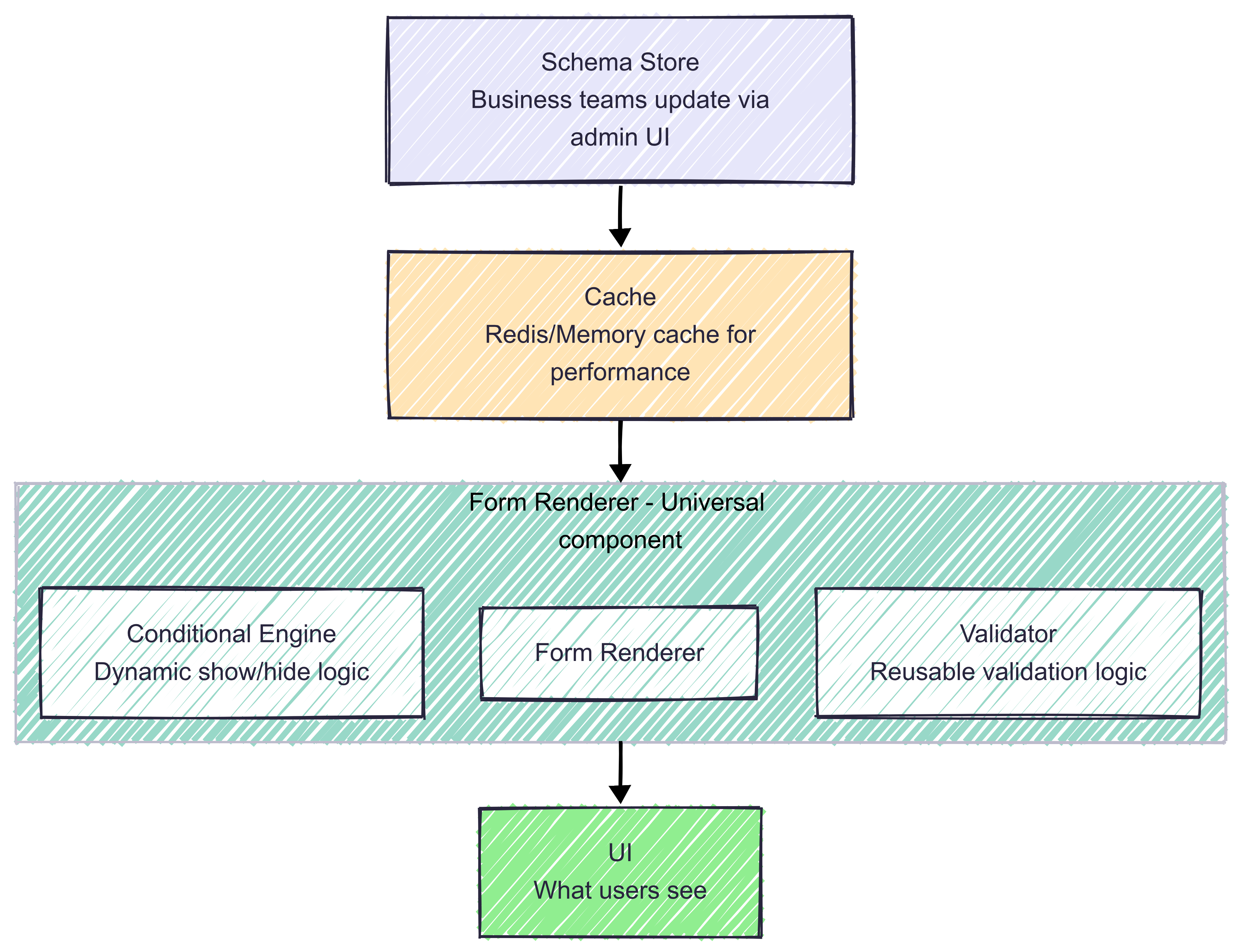

Schema-driven design approach where one schema definition automatically generates forms, validation, documentation, and database structures.

Schema-driven design approach where one schema definition automatically generates forms, validation, documentation, and database structures.

The solution is elegantly simple, but the impact is profound: describe your data once, use it everywhere. With schema-driven design, you define the shape of your data in a single place, and everything else (forms, validation, APIs, databases, documentation) flows from that definition.

# One schema drives everything

customer_onboarding:

fields:

- name: bvn

type: string

required: true

validation: { pattern: "^[0-9]{11}$" }

ui: { label: "Bank Verification Number" }

db: { unique: true, index: true }

- name: account_type

type: enum

options: [savings, current, domiciliary]

ui: { type: radio }

db: { default: savings }

From this single schema, you automatically generate:

- React Components: Type-safe forms with proper validation

- Database Migrations: Columns, indexes, and constraints

- API Documentation: OpenAPI specs with examples

- Backend Validation: Consistent rules across all services

- TypeScript Interfaces: Full type safety

- Test Data Factories: Realistic test data that matches production

// components/UniversalForm.tsx - Schema-driven approach

function UniversalForm({ schema }) {

return (

<form>

{schema.fields.map(field => <FormField key={field.name} {...field} />)}

</form>

);

}

// Auto-generated from schema

interface CustomerOnboarding {

bvn: string;

account_type: 'savings' | 'current' | 'domiciliary';

}

Dynamic Validation

Different markets have complex validation rules. Phone numbers alone are a challenge:

{

"phone_validation": {

"ng": ["^0[789]0\\d{8}$", "^\\+234[789]0\\d{8}$"],

"ke": ["^07\\d{8}$", "^\\+2547\\d{8}$"]

}

}

Schema-based validation adapts to changing requirements without code modifications.

Conditional Logic

Business requirements are rarely linear. “If they select business account, show tax fields. If revenue is over X, require additional documents. If they’re in a regulated industry, add compliance questions.”

{

"fields": [

{ "name": "account_type", "type": "select", "options": ["individual", "business"] },

{ "name": "tax_id", "show_when": { "account_type": "business" } },

{ "name": "audited_financials", "show_when": {

"and": [{ "account_type": "business" }, { "revenue": { "gt": 1000000 }}]

}}

]

}

The business team can now map out their requirements in a format they understand. No more “I need engineering to add a field.” They define it, test it in staging, and ship it.

Multi-Tenant Flexibility

Different markets and customers need different fields without code changes. This is crucial when you’re serving diverse global markets where financial institutions in different countries have completely different requirements:

tenant_schemas:

base: { fields: [name, email, phone] }

nigeria_bank:

extends: base

custom: [{ name: bvn, required: true }, { name: nin }]

telco_partner:

extends: base

custom: [{ name: mobile_number, pattern: "^[0-9]{10,15}$" }]

Each tenant gets their exact requirements without affecting others. When a new partner joins, you configure their schema, not code their solution.

Multi-Step Wizards

Users with limited bandwidth can’t load a 50-field form at once. You need smart, progressive disclosure:

{

"wizard": "business_onboarding",

"steps": [

{ "id": "basic", "fields": ["name", "tax_id"] },

{ "id": "owners", "fields": ["owner_name"], "repeatable": true },

{ "id": "docs", "fields": ["certificate"], "skip_if": { "type": "informal" }}

]

}

Each step loads independently. Progress saves automatically. Users can resume later, critical when data costs are high and connections are unreliable.

Table Generation

This applies beyond forms. Tables, reports, dashboards, everything becomes configurable:

{

"table": "transactions",

"columns": [

{ "key": "date", "type": "datetime", "format": "DD MMM" },

{ "key": "amount", "type": "currency" },

{ "key": "status", "type": "badge" }

],

"filters": ["date_range", "status"],

"actions": [{ "label": "Export", "formats": ["csv", "pdf"] }]

}

Implementation

Building this in practice:

// src/forms/SchemaFormRenderer.ts

class SchemaFormRenderer {

renderField(field) {

if (!this.shouldShowField(field)) return null;

const renderer = this.fieldRenderers[field.type] || this.defaultRenderer;

return renderer(field, this.data[field.name]);

}

validateField(field, value) {

const rules = field.validation || {};

if (rules.required && !value) return `${field.label} is required`;

if (rules.pattern && !new RegExp(rules.pattern).test(value)) {

return `${field.label} format is invalid`;

}

return null;

}

}

Common Pitfalls

The Over-Engineering Trap: Don’t try to make everything configurable on day one. Start with the fields that change most often. Add configuration as patterns emerge.

Performance Concerns: “Won’t loading schemas be slow?” Cache aggressively. Schemas change infrequently. Load once, use everywhere.

Type Safety: In TypeScript? Generate types from your schemas:

// Generated from schema

interface OnboardingForm {

national_id: string;

tax_id?: string;

account_type: 'savings' | 'current' | 'investment';

}

Complex Validation: Some rules are too complex for JSON. That’s okay:

{

"validation": {

"custom": "validateNationalId",

"async": true,

"message": "National ID verification failed"

}

}

The validation logic lives in code. The configuration determines when to use it.

When to Use It

Perfect for:

- Multi-market platforms

- Heavily regulated industries

- Rapid iteration environments

- Business-user-facing configurations

Skip it for:

- Simple, static forms

- Internal tools that rarely change

- Prototypes and MVPs

The Cultural Shift

Schema-driven design changes how teams think about data collection. Instead of hardcoding forms, developers build flexible systems. Product managers define requirements as schemas, not mockups. Compliance teams update forms without touching code.

The real transformation happens when non-technical teams realize they can make changes themselves. A compliance officer adds a required field for new regulations. A country manager adjusts forms for local requirements. A product manager tests new onboarding flows. All without a single Jira ticket.

This autonomy breaks down the traditional walls between business and engineering. Forms become living documents that evolve with the business, not frozen artifacts waiting for the next sprint. That’s when schema-driven design reveals its true power - turning everyone into a contributor.

Principle 5 - Event-Driven Architecture: Adding Features Without Breaking Everything

Design systems around events (“order_placed,” “payment_received”) instead of tightly coupled workflows.

— Adia Sowho

Imagine Black Friday. Your payment system is humming along nicely when suddenly the inventory service slows down. In a tightly coupled system, that slowdown ripples through everything. Payment processing slows. Customers retry. Load increases. Before you know it, your entire platform is down during your biggest sales day of the year.

The fascinating thing is, the code isn’t broken. The architecture is. Tightly coupled services are like dominoes: knock one over and they all fall. Events change this dynamic completely.

The Problem

Here’s how most payment systems start:

# app/services/legacy_payment_processor.rb - Tightly coupled

def process_payment(payment_data)

payment = create_payment_record(payment_data)

inventory_service.decrease_stock(payment.items) # Blocks if slow

email_service.send_receipt(payment.customer_email) # Fails if down

sms_service.notify_merchant(payment.merchant_phone) # Single point of failure

analytics_service.track_purchase(payment) # Maintenance = downtime

loyalty_service.add_points(payment.customer_id)

payment

end

This looks clean and logical. It’s also a ticking time bomb. Every service call is a potential point of failure that can bring down your entire payment flow. When that analytics database went under maintenance, payments stopped working. When the SMS gateway had network issues in one region, customers everywhere couldn’t complete purchases.

The Solution

Event-driven architecture flips this model. Instead of orchestrating a sequence of calls, you publish events and let interested services react:

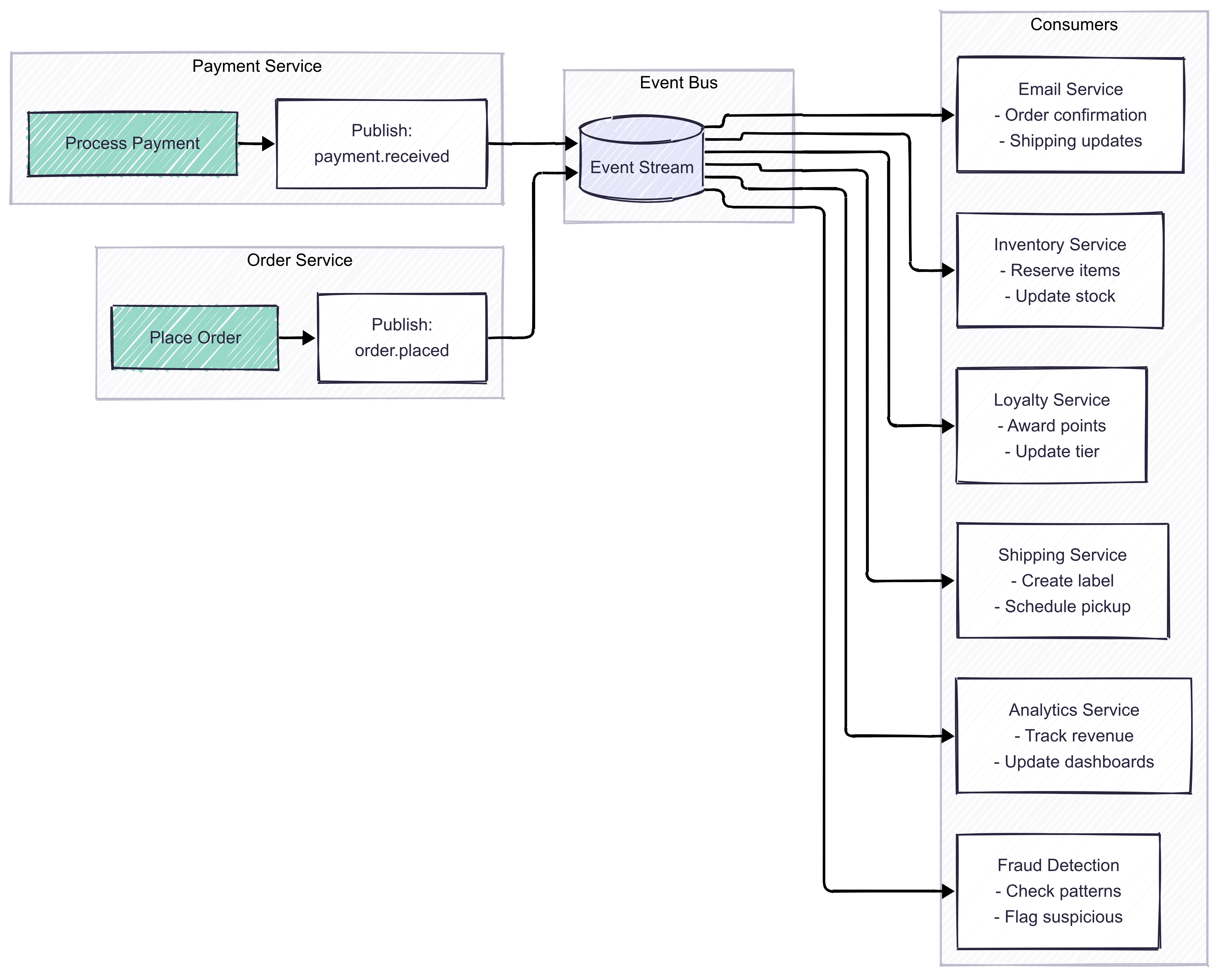

Event-driven architecture comparison showing the transformation from tightly coupled synchronous calls to decoupled event-driven communication.

Event-driven architecture comparison showing the transformation from tightly coupled synchronous calls to decoupled event-driven communication.

# app/services/event_driven_payment_processor.rb - Decoupled

def process_payment(payment_data)

payment = create_payment_record(payment_data)

publish_event("payment_completed", payment.to_h)

payment # Returns immediately

end

Now each service subscribes to relevant events and handles them independently:

# app/services/event_subscribers.rb - Independent services

subscribe("payment_completed") do |event|

decrease_stock(event["items"]) # Inventory: fails independently

end

subscribe("payment_completed") do |event|

send_receipt(event["customer_id"]) # Email: retries on its own

end

subscribe("payment_completed") do |event|

analytics_queue.add(event) # Analytics: processes in batches

end

With event-driven architecture, service failures are isolated. One service’s problem doesn’t cascade to others.

Events vs Commands

This distinction took me years to truly understand, and it’s critical for global markets where systems need to integrate with banks, telcos, and government services that you don’t control.

The distinction is subtle but powerful:

- Commands tell systems what to do: “charge_customer”, “send_sms”, “update_balance”

- Events state what happened: “payment_completed”, “sms_sent”, “balance_updated”

Commands create coupling. Events preserve independence. When you send a command, you’re dependent on that service being available and succeeding. When you publish an event, you’re simply stating a fact, and interested parties can react when they’re able.

Implementing Event-Driven Architecture

You probably already have Redis running for caching. Turns out Redis Streams does everything you need for event-driven architecture: persistence, consumer groups, ordering, atomic operations. That’s what we’ll use here. When you’re processing millions of events per second, then look at Kafka or cloud solutions. Not before.

Building Your Event Bus

Your event bus is the backbone - it publishes events to streams and lets multiple services consume them independently. Each service gets its own consumer group, tracking what it’s already processed:

# app/services/redis_event_bus.rb

class RedisEventBus

def publish(event_type, data)

event = {

event_id: "evt_#{SecureRandom.hex(8)}",

type: event_type,

timestamp: Time.now.utc.iso8601,

data: data

}

@redis.xadd("events:#{event_type}", event)

end

def subscribe(event_type, consumer_group)

stream_key = "events:#{event_type}"

# Create consumer group if needed

@redis.xgroup(:create, stream_key, consumer_group, '$') rescue nil

loop do

# Read and process messages

messages = @redis.xreadgroup(consumer_group, "consumer-#{Process.pid}",

{ stream_key => '>' }, block: 1000)

messages&.each do |stream, events|

events.each do |message_id, data|

yield(JSON.parse(data['data']))

@redis.xack(stream_key, consumer_group, message_id)

end

end

end

end

end

Ordered Event Processing

Some events must be processed in order. Think bank transactions - you can’t withdraw before a deposit clears. Use entity-specific streams to guarantee ordering per customer, account, or any business entity:

# app/services/ordered_event_publisher.rb

class OrderedEventPublisher

def publish_ordered(entity_id, event_type, data)

# Use entity-specific streams for guaranteed ordering

stream_key = "events:#{event_type}:#{entity_id}"

@redis.xadd(stream_key, { type: event_type, data: data.to_json })

end

def process_ordered(entity_id, event_type, consumer_group)

stream_key = "events:#{event_type}:#{entity_id}"

# Process one at a time for strict ordering

messages = @redis.xreadgroup(consumer_group, "consumer-1",

{ stream_key => '>' }, count: 1)

# Messages from same stream always processed in order

end

end

Event Sourcing

Regulators want to know how you reached your current state, not just what it is. Event sourcing stores events that led to current state instead of the state itself. Every change becomes an immutable fact in your event stream:

# app/models/redis_event_sourced_account.rb

class RedisEventSourcedAccount

def append_event(event_type, data)

@redis.xadd("account:#{@account_id}:events", {

type: event_type,

timestamp: Time.now.utc.iso8601,

data: data.to_json

})

end

def get_current_state

# Replay all events to rebuild current state

events = @redis.xrange(@stream_key, '-', '+')

state = { balance: 0 }

events.each do |_, event_data|

case event_data['type']

when 'money_deposited' then state[:balance] += JSON.parse(event_data['data'])['amount']

when 'money_withdrawn' then state[:balance] -= JSON.parse(event_data['data'])['amount']

end

end

state

end

def get_state_at(timestamp)

# Time travel - replay events up to timestamp

events = @redis.xrange(@stream_key, '-', '+')

events.take_while { |_, e| e['timestamp'] <= timestamp }

.reduce({ balance: 0 }) { |state, (_, event)| apply_event(state, event) }

end

end

This gives you superpowers:

- Complete audit trail: Every change is permanently stored in Redis Streams

- Time travel: Reconstruct state at any point using xrange with timestamps

- Debugging: Replay events from Redis to reproduce issues

- Compliance: Full event history available for regulators

Handling Failures

Events fail. Networks partition. Services crash. Handle failures with these patterns:

Dead Letter Queues

When events fail repeatedly, you need somewhere to put them for investigation. Dead letter queues prevent poison messages from blocking your entire system:

# app/services/redis_failure_handler.rb

class RedisFailureHandler

def process_with_retry(stream_key, consumer_group)

# Check pending messages for retries

pending = @redis.xpending(stream_key, consumer_group, '-', '+', 100)

pending.each do |message_id, _, idle_time, delivery_count|

if delivery_count >= @max_retries

# Move to DLQ after max retries

move_to_dlq(stream_key, message_id, consumer_group)

elsif idle_time > 30000 # Retry if idle > 30 seconds

# Claim and retry

@redis.xclaim(stream_key, consumer_group, "consumer", 30000, message_id)

end

end

end

def move_to_dlq(stream_key, message_id, consumer_group)

# Get failed message and move to DLQ

message = @redis.xrange(stream_key, message_id, message_id).first

@redis.xadd("#{stream_key}:dlq", message[1].merge('failed_at' => Time.now.iso8601))

@redis.xack(stream_key, consumer_group, message_id)

end

end

Idempotent Processing

Atomic operations make idempotent processing straightforward:

# app/services/redis_idempotent_processor.rb

class RedisIdempotentProcessor

def process_once(event_id, &block)

processing_key = "processing:#{event_id}"

completed_key = "completed:#{event_id}"

# Already done?

return :already_completed if @redis.exists?(completed_key)

# Try to acquire lock with SET NX (atomic)

if @redis.set(processing_key, Process.pid, nx: true, ex: 300)

result = yield

@redis.set(completed_key, "done", ex: 86400) # Cache for 24h

@redis.del(processing_key)

:success

else

:processing # Someone else has the lock

end

end

end

# Usage: process each payment exactly once

processor.process_once(payment_id) do

charge_customer(amount)

send_receipt(email)

end

Scaling Considerations

Redis Streams is simple and robust enough for most use cases. It can handle tens of thousands of events per second on a single Redis instance, with built-in persistence, consumer groups, and delivery guarantees.

When you do hit critical scale (millions of events per second, petabytes of data retention, complex routing requirements), you can migrate to specialized solutions:

| Feature | Redis Streams | Apache Kafka | AWS Kinesis | GCP Pub/Sub |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setup Complexity | Simple (likely already have Redis) | Complex (Zookeeper, brokers, topics) | Managed service | Managed service |

| Throughput | 10-100K msgs/sec | 1M+ msgs/sec | 1M+ msgs/sec | 1M+ msgs/sec |

| Retention | Limited by memory | Unlimited (disk) | 365 days | 7 days |

| Ordering | Per stream | Per partition | Per shard | Per ordering key |

| Consumer Groups | Built-in | Built-in | Via applications | Built-in |

| Operational Cost | Low | High | Pay-per-use | Pay-per-use |

| Team Learning Curve | Minimal | Steep | Moderate | Moderate |

Start with Redis Streams. It’s production-ready, battle-tested, and sufficient for 99% of applications. When you genuinely need Kafka’s scale or a cloud provider’s managed service, the migration path is clear because the concepts (streams, consumer groups, acknowledgments) transfer directly.

Migration Strategy

Migrate gradually:

Step 1: Event Publishing

Start by publishing events alongside existing code:

# app/services/payment_legacy_with_events.rb

def process_payment_legacy(payment_data)

# Existing code remains unchanged

payment = create_payment_record(payment_data)

inventory_service.decrease_stock(payment.items)

email_service.send_receipt(payment.customer_email, payment)

# ADD: Publish event for new consumers

publish_event("payment_completed", payment.to_h)

payment

end

Step 2: Event Consumers

Build new features as event-driven from day one:

# app/services/loyalty_points_subscriber.rb

# New loyalty program is event-driven

subscribe("payment_completed") do |event|

points = calculate_points(event["amount"])

award_points(event["customer_id"], points)

publish_event("loyalty_points_awarded", {

customer_id: event["customer_id"],

points: points,

trigger: event["payment_id"]

})

end

Step 3: Service Extraction

Move existing functionality to events one service at a time:

# app/services/payment_hybrid_processor.rb

def process_payment_hybrid(payment_data)

payment = create_payment_record(payment_data)

# Inventory now event-driven

publish_event("payment_completed", payment.to_h)

# These still synchronous (for now)

email_service.send_receipt(payment.customer_email, payment)

payment

end

Step 4: Full Migration

Eventually, the core flow just publishes events:

# app/services/payment_final_processor.rb

def process_payment(payment_data)

payment = create_payment_record(payment_data)

publish_event("payment_completed", payment.to_h)

payment

end

Common Anti-Patterns

The Event Spaghetti: Don’t create events for everything. “user_clicked_button” is not a business event. “order_placed” is.

The Distributed Monolith: If your services can’t function without immediate responses to events, you haven’t decoupled, you’ve just made things more complex.

The Event Mutation: Never modify events after publishing. If you need to correct something, publish a compensation event.

The Missing Schema: “We’ll add structure later” never works. Define your event schema from day one.

The Synchronous Event: Using events for request-response patterns defeats the purpose. If you need immediate responses, use API calls.

When Not to Use Events

Event-driven architecture isn’t always appropriate:

- Simple CRUD operations: Don’t over-engineer

- Synchronous validations: “Is this email unique?” needs immediate response

- Real-time UI updates: Use WebSockets or Server-Sent Events instead

- Small, single-team projects: The complexity isn’t worth it

The Cultural Shift

The hardest part isn’t technical, it’s mental. Developers used to tracing through linear code struggle with distributed flows.

Build an event viewer showing real-time event flow. Create dashboards showing event rates and processing times. Use correlation IDs to trace entire flows. Generate sequence diagrams from event logs.

When developers can see events flowing through the system, understanding follows. When they see one service fail while others continue, they become believers.

Events are facts about what happened. Facts don’t fail, they don’t timeout, and they don’t depend on other services being available. Build on facts, and you build on solid ground.

Principle 6 - Separation of Concerns: When Marketing Can Move Without Breaking Engineering

Keep user interface, business logic, and data access strictly separated.

— Adia Sowho

The fastest way to ship a feature is often to put everything in one place. The UI component that handles the payment? It also calculates discounts, updates inventory, and sends emails. It works… until marketing wants to change the discount logic and accidentally breaks payment processing.

The Problem

We’ve all written code like this when rushing to meet deadlines:

// components/CheckoutPage.tsx - The tightly coupled approach

function CheckoutPage({ userId }) {

const handleCheckout = async () => {

const cart = await db.query(`SELECT * FROM carts WHERE...`);

if (cart.total > 10000) discount = cart.total * 0.1;

await db.query(`UPDATE inventory SET...`);

if (paymentMethod === 'mpesa') {

// 200 lines of payment logic in UI component

}

await sendEmail(user.email, 'Order Confirmation');

};

return <button onClick={handleCheckout}>Pay Now</button>;

}

This looks straightforward, but it’s a maintenance nightmare. Want to test the discount logic? You need a full database. Want to reuse the payment flow in your mobile app? You’re copying and pasting code. When the payment provider changes their API, you’re hunting through UI components to find all the places that need updates.

The Three Layers

Separation of Concerns means organizing your code into distinct layers, each with a single responsibility. Think of it like a restaurant kitchen: you don’t want the sous chef handling payments, the server cooking steaks, or the manager washing dishes. Each role has clear boundaries and responsibilities.

Three-layer separation of concerns architecture with clear boundaries and responsibilities for presentation, business logic, and data access layers.

Three-layer separation of concerns architecture with clear boundaries and responsibilities for presentation, business logic, and data access layers.

Layer 1: Presentation Layer (UI)

- Responsibility: Display data and capture user input

- Knows about: How to render components, handle user interactions

- Doesn’t know about: Database schemas, business rules, external APIs

// components/CheckoutPage.tsx - Clean separation

function CheckoutPage({ onCheckout, cart, paymentMethods }) {

const handleCheckout = async (method) => {

const result = await onCheckout(method); // UI doesn't know HOW

if (result.success) router.push('/confirmation');

};

return (

<div>

<CartSummary cart={cart} />

<PaymentMethodSelector onSelect={handleCheckout} />

</div>

);

}

Layer 2: Business Logic Layer (Domain)

- Responsibility: Enforce business rules and orchestrate operations

- Knows about: Business rules, workflows, validations

- Doesn’t know about: UI frameworks, database implementations, HTTP details

# app/services/checkout_service.rb - Business logic layer

class CheckoutService

def process_checkout(user_id, payment_method)

cart = @cart_repo.find_by_user(user_id) # No SQL here

discount = calculate_discount(cart) # Business rules

ActiveRecord::Base.transaction do

reservation = @inventory_service.reserve(cart.items)

payment = @payment_processor.charge(cart.total - discount)

if payment.success?

order = create_order(cart, payment)

publish_event("order.completed", order)

end

end

end

def calculate_discount(cart)

return cart.total * 0.2 if cart.user.is_vip?

return cart.total * 0.1 if cart.total > 10000

0

end

end

Layer 3: Data Access Layer (Persistence)

- Responsibility: Store and retrieve data

- Knows about: Database schemas, query optimization, caching

- Doesn’t know about: Business rules, UI requirements

# app/repositories/cart_repository.rb - Data layer

class CartRepository

def find_by_user(user_id)

record = Cart.includes(:items).where(user_id: user_id).first

return nil unless record

# Return domain objects, not ActiveRecord

DomainCart.new(id: record.id, items: map_items(record.items))

end

def save(cart)

Cart.find_or_create_by(id: cart.id).update!(cart.attributes)

end

end

Common Pitfalls

Anemic Domain Models

Don’t create domain objects that are just data holders:

# Bad - Anemic model

class Order

attr_accessor :items, :total, :status

end

# Good - Rich domain model

class Order

def initialize(items)

@items = items

@status = :pending

end

def confirm_payment(payment_reference)

raise "Order already paid" if paid?

@payment_reference = payment_reference

@status = :paid

@paid_at = Time.current

end

def can_be_cancelled?

pending? || (paid? && paid_within_last_hour?)

end

private

def paid?

@status == :paid

end

def pending?

@status == :pending

end

end

Leaky Abstractions

Don’t let implementation details leak through layers:

# Bad - SQL leaking into business logic

class OrderService

def find_recent_orders(user)

Order.joins(:user)

.where('created_at > ?', 30.days.ago)

.where(user_id: user.id)

.order('created_at DESC')

end

end

# Good - Clean abstraction

class OrderService

def find_recent_orders(user)

@order_repository.find_recent_for_user(user, days: 30)

end

end

Wrong Dependencies

Never let lower layers depend on higher layers:

# Bad - Repository knows about controller concerns

class OrderRepository

def find_for_api(params)

orders = Order.all

orders = orders.page(params[:page]) if params[:page]

orders = orders.where(status: params[:status]) if params[:status]

orders

end

end

# Good - Repository provides basic operations

class OrderRepository

def find_by_criteria(status: nil, limit: nil, offset: nil)

scope = Order.all

scope = scope.where(status: status) if status

scope = scope.limit(limit).offset(offset) if limit

scope

end

end

# Controller handles API concerns

class OrdersController

def index

orders = repository.find_by_criteria(

status: params[:status],

limit: per_page,

offset: page_offset

)

render json: OrderSerializer.new(orders, pagination: pagination_meta)

end

end

Migration Path

You don’t need to rewrite everything. Start with new features:

Step 1: Identify Boundaries

Pick one area of your application (e.g., checkout, user management, inventory).

Step 2: Extract Logic

Create service objects for complex operations:

# Start by extracting logic from controllers

class CheckoutController

def create

# Before: 200 lines of mixed concerns

# After:

result = CheckoutService.new.process(current_user, params)

if result.success?

redirect_to success_path

else

render :error

end

end

end

Step 3: Define Interfaces

Define clear contracts between layers:

# Define what each layer needs

module Contracts

CheckoutRequest = Struct.new(:user_id, :payment_method, :items)

CheckoutResponse = Struct.new(:success?, :order, :error)

end

Step 4: Migrate Gradually

Move one piece at a time, maintaining backward compatibility:

class PaymentService

def process(amount, customer, method)

if Feature.enabled?(:new_payment_architecture)

# New separated architecture

strategy = PaymentStrategyFactory.for_method(method)

strategy.charge(amount, customer)

else

# Old mixed concerns (temporary)

LegacyPaymentProcessor.process(amount, customer, method)

end

end

end

Real-World Example

Separation of concerns enables a commerce platform to serve multiple channels:

# Domain layer - shared across all channels

module Domain

class ProductCatalog

def search(query, filters = {})

products = @repository.search(query)

products = apply_filters(products, filters)

products = apply_business_rules(products)

products

end

private

def apply_business_rules(products)

# Hide products not available in user's country

# Apply pricing rules

# Check inventory levels

products.select { |p| p.available_in?(@context.country) }

end

end

end

# Web presentation layer

class ProductsController < ApplicationController

def index

products = catalog.search(params[:q], web_filters)

render_with_seo_optimization(products)

end

end

# Mobile API layer

class Api::ProductsController < ApiController

def index

products = catalog.search(params[:q], mobile_filters)

render json: MobileProductSerializer.new(products)

end

end

# USSD layer

class UssdProductHandler

def handle_search(session, input)

products = catalog.search(input, ussd_filters)

format_for_ussd(products, max_length: 160)

end

end

# WhatsApp bot layer

class WhatsappProductBot

def handle_search(message)

products = catalog.search(message.text, whatsapp_filters)

format_as_whatsapp_carousel(products)

end

end

The Cultural Shift

Separation of concerns creates clear ownership boundaries. Frontend teams own user experience. Backend teams own business logic. Infrastructure teams own reliability. Marketing owns content. Each team moves at their own pace without blocking others.

This independence transforms how teams collaborate. Instead of waiting for backend changes, frontend teams build against contracts. Instead of hardcoding content, developers read from configuration. Instead of coupling systems, teams publish events.

The culture evolves from “Let me check with the other team” to “Here’s our interface, build what you need.” Teams become truly autonomous, responsible for their domain but not blocked by others. That’s when velocity really takes off.

Principle 7 - Domain-Driven Design: Speaking the Same Language

Structure your code around business concepts, not whatever is easiest to code at the moment.

— Adia Sowho

Have you ever been in a meeting where the business team talks about “wallets” and “float accounts,” but your code has UserMoneyHolder and TempFunds? Where they say “initiate reversal” but your method is called undo_transaction()? This disconnect creates a constant translation layer between what the business wants and what the code does.

Every conversation becomes a game of telephone. Feature requests get lost in translation. Bug reports turn into archaeological expeditions. In regulated industries like fintech, this confusion isn’t just inefficient, it can lead to compliance failures.

The Problem

Here’s what happens when code ignores business language:

# app/models/user_money_thing.rb - Developer language

class UserMoneyThing < ApplicationRecord

def add_money(amount) # Business calls this "credit"

self.balance += amount

end

def remove_money(amount) # Business calls this "debit"

raise "Not enough money" if balance < amount # "insufficient funds"

self.balance -= amount

end

def do_the_thing_for_month_end # "settlement reconciliation"?

# 200 lines of mystery logic

end

end

When a regulator asks “Show me how you handle dormant wallets,” you’re grep-ing through code for inactive, unused, old, abandoned, hoping you find the right logic. When they ask about your “know your customer” process, you’re searching for kyc, verification, identity, compliance, unsure which one is current.

The Solution

Domain-Driven Design (DDD) means structuring your code to mirror the business domain. When the business says “wallet,” your code says Wallet. When they describe a process, your code implements that exact process with the same names.

Ubiquitous Language

The core of DDD is establishing a shared language between business and tech:

# app/models/wallet.rb - Business language

class Wallet < ApplicationRecord

def credit(amount, reference) # Business term as method name

transactions.create!(type: 'credit', amount: amount)

update!(balance: balance + amount)

end

def debit(amount, reference)

raise InsufficientFundsError if available_balance < amount

transactions.create!(type: 'debit', amount: amount)

update!(balance: balance - amount)

end

def mark_as_dormant # Exact business terminology

update!(status: 'dormant') if inactive_for?(180.days)

end

def settlement_reconciliation

SettlementReconciliation.new(self).perform

end

end

Now when the business team says “We need to adjust how we handle dormant wallets,” you know exactly where to look: the mark_as_dormant method. No translation needed.

Bounded Contexts

This is where domain-driven design gets really interesting. In fintech, the same word often means different things in different contexts. “Transaction” means something different to:

- The payments team (money movement)

- The accounting team (ledger entry)

- The compliance team (reportable event)

- The customer service team (customer activity)

This isn’t a bug, it’s a feature. DDD handles this through Bounded Contexts, clearly defined boundaries where specific meanings apply. Think of bounded contexts like languages - “bank” means something different to a financial analyst than to a river guide:

# Bounded Contexts - Same word, different meanings

module Payments

class Transaction # Money movement

def process

validate_kyc

perform_money_movement

notify_parties

end

end

end

module Accounting

class Transaction # Ledger entry

def post

create_journal_entries

update_trial_balance

end

end

end

module Compliance

class Transaction # Reportable event

def screen

check_sanctions

assess_risk

report_if_required

end

end

end

Each context has its own Transaction class with context-specific behavior. No confusion, no conflicts.

Here’s how they work together when a customer sends money:

# app/services/money_transfer_coordinator.rb

class MoneyTransferCoordinator

def execute(sender_id, recipient_id, amount)

# 1. Payments context: Execute the money movement

payment_txn = Payments::Transaction.new(sender_id, recipient_id, amount)

payment_result = payment_txn.process

# 2. Accounting context: Record in the ledger

accounting_txn = Accounting::Transaction.new(

debit: sender_id,

credit: recipient_id,

amount: amount,

reference: payment_result.id

)

accounting_txn.post

# 3. Compliance context: Check for suspicious activity

compliance_txn = Compliance::Transaction.new(

payment_id: payment_result.id,

amount: amount,

parties: [sender_id, recipient_id]

)

compliance_txn.screen

# 4. Customer context: What the customer sees

CustomerActivity.create(

customer_id: sender_id,

description: "Sent #{amount} to #{recipient_id}",

reference: payment_result.id

)

end

end

Same word, four different meanings, all working together. Each team owns their context, speaks their language, and the coordinator translates between them.

Aggregates

In DDD, an Aggregate is a cluster of related objects that we treat as a single unit. In mobile money systems, a MobileMoneyAccount aggregate might look like:

# app/domains/mobile_money/account_aggregate.rb

module MobileMoney

class AccountAggregate # Keeps related things together

attr_reader :account, :wallet, :kyc_profile, :limits

def register_customer(details)

ActiveRecord::Base.transaction do

@account.update!(details)

@kyc_profile.initiate_verification

@wallet.activate

publish_event(CustomerRegistered.new(account))

end

end

def send_money(amount, recipient, pin)

validate_pin(pin)

validate_daily_limit(amount)

TransferService.execute(self, recipient, amount)